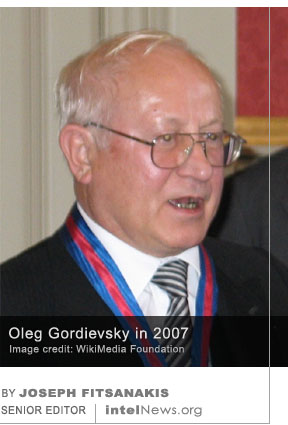

Death of Soviet defector Gordievsky not seen as suspicious, British police say

March 24, 2025 8 Comments

BRITISH MEDIA REPORTED THE death on Saturday of Oleg Gordievsky, arguably the most significant double spy of the closing stages of the Cold War, whose disclosures informed the highest executive levels of the West. Having joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, Gordievsky became increasingly disillusioned with the Soviet system of rule following the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia.

BRITISH MEDIA REPORTED THE death on Saturday of Oleg Gordievsky, arguably the most significant double spy of the closing stages of the Cold War, whose disclosures informed the highest executive levels of the West. Having joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, Gordievsky became increasingly disillusioned with the Soviet system of rule following the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia.

By 1974, Gordievsky had established contact with Danish and British intelligence and was regularly providing information to Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). After 1982, when Gordievsky was posted to the Soviet embassy in London, MI6 deliberately subverted his superiors at the embassy by expelling them. This effectively enabled Gordievsky to take their place and rise to the position of resident-designate of the KGB station in London.

Intelligence historians credit Gordievsky’s intelligence with having shaped the strategic thinking of British and American decision-makers in relation to the Soviet Union. Crucially, Gordievsky’s warnings to MI6 that the Kremlin was genuinely concerned about a possible nuclear attack by the West prompted British and American leaders to temper their public rhetoric against the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s. Some even credit Gordievsky with having helped the West avoid a nuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union.

In 1985, while undergoing interrogation by the Soviet authorities, Gordievsky was smuggled out of Russia by British intelligence, hidden inside a car that made its way to Finnish territory. He was subsequently sentenced in absentia to death for treason against the Soviet Union. In 1991, following an agreement between British and Soviet authorities, Gordievsky’s wife and daughters were allowed to join him in England.

According to Surrey Police, officers were called to a residential address in the city of Godalming on Tuesday March 4, where they found 86-year-old Gordievsky’s body, surrounded by members of his family. Godalming is a small market town in southeastern England, located around 30 miles from London. Surrey Police noted in a statement that the investigation into Gordievsky’s death was led by counterterrorism officers. However, his death was “not being treated as suspicious”.

Gordievsky spent nearly 40 hours in a coma in 2007, from which he eventually recovered. He subsequently claimed that he had been poisoned after taking sleeping pills tainted with a lethal toxin, which had been supplied to him by a man he referred to as a “business associate” with a Russian background.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 24 March 2025 | Permalink

Oleg Gordievsky was one of the most impactful KGB officers ever to defect to the West. At a critical juncture in the Cold War, his intelligence played a crucial role in averting a potential Third World War, which could have escalated into a nuclear conflict. REST IN PEACE with thanks from the last few standing at FaireSansDire & Pemberton’s People.

May this hero have a deserved rest.

It would be both interesting and instructive to understand how he so adroitly avoided a Service 7 “encounter” all those years.

Just as Trump goes into secret Ukrainian negotiations with Putin, this happens.

Young Oleg was only 86. This is suspicious!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oleg_Gordievsky

En tant qu’officer sous-traitant Dod/cui.

Gordievsky a d’abord attiré l’attention du M-16 après une dénonciation d’une espionne tchécoslovaque, Standa Kaplan, qui avait fait défection au Canada. Kaplan a mentionné Gordievsky comme un vieil ami de l’académie du KGB, où ils remettaient ensemble en question la direction prise par le Kremlin. À ce moment-là, Gordievsky était un officier du KGB attaché à l’ambassade soviétique à Copenhague ; En 1972, il a réagi favorablement aux approches délicates des officiers du MI6 dans la capitale danoise, après que des écoutes téléphoniques ont révélé que dans des appels à sa femme à Moscou, il avait exprimé une inquiétude croissante au sujet des actions du Kremlin, mentionnant spécifiquement l’invasion de la Tchécoslovaquie en 1968. Il a commencé à espionner pour le compte de la Grande-Bretagne lorsqu’il est retourné à Moscou en 1974.

En 1985, suspecté de trahison, il a été rappelé à Moscou mais a réussi à s’échapper vers le Royaume-Uni, où il a vécu sous protection jusqu’à son décès en mars 2025

Salut Pete, En tant qu’officier sous-traitant du DoD/CUI, je souhaite rendre hommage à Oleg Gordievsky, décédé récemment à l’âge de 86 ans. Pour certains, il est considéré comme un héros pour avoir contribué à prévenir un conflit nucléaire ; pour d’autres, il n’était ni plus ni moins qu’un transfuge des services de renseignement. Pour ma part, il fait partie de ces agents méritant le respect, et j’adresse mes condoléances à sa famille.

Actuellement, des négociations secrètes sont en cours avec Vladimir Poutine, et les priorités se situent ailleurs plutôt qu’autour d’actes suspects. L’ancien agent du KGB et du FSB, Gordievsky, n’était plus une menace constante pour la Russie, surtout après avoir survécu à une tentative d’assassinat présumée en 2007, où il est tombé dans le coma pendant 36 heures. Suite à cet incident, le MI6 avait renforcé sa sécurité/

PASCAL/ LEMBRE CUI/

PASCAL’s comments, when translated into English, are particularly relevant:

“As a DOD/CUI contract officer.

Gordievsky first came to the attention of MI6 after a tip-off from a Czechoslovakian spy, Standa Kaplan, who had defected to Canada. Kaplan mentioned Gordievsky as an old friend from the KGB Academy, where they had been questioning the direction the Kremlin was taking. At the time, Gordievsky was a KGB officer attached to the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen; In 1972, he responded favorably to the sensitive approaches of MI6 officers in the Danish capital, after wiretaps revealed that in calls to his wife in Moscow, he had expressed growing concern about the Kremlin’s actions, specifically mentioning the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. He began spying for Britain when he returned to Moscow in 1974.

In 1985, suspected of treason, he was recalled to Moscow but managed to escape to the UK, where he lived under protective custody until his death in March 2025.

Hi Pete, As a DoD/CUI contracting officer, I would like to pay tribute to Oleg Gordievsky, who recently passed away at the age of 86. To some, he is considered a hero for helping to prevent a nuclear conflict; For others, he was nothing more than a defector from the intelligence services. For my part, he is one of those agents deserving of respect, and I offer my condolences to his family.

Currently, secret negotiations are underway with Vladimir Putin, and priorities are elsewhere rather than suspicious actions. Former KGB and FSB agent Gordievsky was no longer a constant threat to Russia, especially after surviving an alleged assassination attempt in 2007, in which he fell into a 36-hour coma. Following this incident, MI6 had increased his security.

PASCAL/ LEMBRE CUI/”

See a reference to Standa Kaplan in the 6th paragraph of this review of the excellent book The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/sep/19/the-spy-and-the-traitor-by-ben-macintyre-review

I think it is a misunderstanding that Gordievsky’s telephone call to his wife took place when he was in Copenhagen and she in Russia? Rather, they were both in Copenhagen. He simply phoned home to her, as far as I understand. It was a deliberate attempt on his part to reach the Danish Intelligence Service. He was pretty sure that they had a wire-tap on the phone to his home (correct guess), and he expressed to her his upset about what was happening (this was in 1968), the Russians putting down the uprising in Prague. His hope was that that would alert the Danish Intelligence Service to him as a possible recruit and that they would manage to contact him. They did indeed have him under observation.

The Danes called in British MI6 and they cooperated when he had been recruited. Their communication took place in Copenhagen, between 1974 and 1978. He was called back to Moscow in 1978. It is not correct that he started working for MI6 when he returned to Moscow; on the contrary, the Brits and the Danes took care not to contact him while he was in the Soviet Union, because that was thought too dangerous for him.

MI6 could not believe their good fortune when Britain received an application for a visa for Oleg Gordievsky early in 1982! He took contact with them when he had been installed in London in the summer, simply by ringing a special telephone number he had memorised before he left Copenhagen. And sure enough the number worked and had a welcome message for him.

Something more about Gordievsky:

I have recently read historian Christopher Andrew’s 850 pages long “The Defence of the Realm. The Authorized History of MI5”. It has a lot about Gordievsky, and Andrew expresses himself very warmly about him – not unexpected, because they cooperated on three books early in the 1990s (the books are about the KGB’s foreign operations). MI5 (the Security Service) and MI6 worked together a lot as ‘handlers’ of Gordievsky while he was a KGB officer in London. Andrew also says that Margaret Thatcher “emphasized her concern for Gordievsky as an individual – not just as an ‘intelligence egg layer’.” He had after all been a double spy for 10 years by then, and was living under strain. That was while Gordievsky was still working at the Soviet embassy in London.

The group of MI5 workers whom Gordievsky had helped particularly on one case “also sent a personal message of gratitude, telling Gordievsky ‘how warmly we feel about him’. Gordievsky replied with equally warm congratulations on the success of the Bettaney investigation, saying that he dreamed of the day when he would be able to meet and talk to the officers of the Security Service: “I don’t know whether such a day will come or not – maybe not. Nevertheless, I would like this idea to be recorded somewhere: that I have underlined my belief that they are the real defenders of democracy in the most direct sense of the word. Therefore it is natural for me to give them whatever help and support I can.” ” – The day came! after he with help had fled Moscow and was assisted to establish himself in Britain. He got to know several of the British Intelligence people as friends.

Back while he was still at the Soviet embassy, there was another unique episode in world history, two years after his contribution to avoiding atomic war: Gorbachev was the new man, and came to London in December 1984, for conferences with Thatcher & co. The embassy provided him with a translator and advisor, they chose Oleg Gordievsky! (he might have been the best English-speaker at the embassy). So Gordievsky, talking with Gorbachev in the evenings about Gorbachev’s thoughts and plans of what to take up the next day, could convey this – truthfully but secretly – to the Brits at night. And the MI6 gave Gordievsky (with permission to tell it to Gorbachev, of course) information about the thoughts and plans of Mrs Thatcher and Foreign Minister Sir Geoffrey Howe. Gordievsky just had to let the Russians think he had got his knowledge from spying on the Brits. So he was briefing both sides, and truthfully. Gorbachev’s visit was a success – he and Thatcher got on very well indeed.

Oleg Gordievsky continued to work for British Intelligence later too, after he had defected . Apparently they though the most useful information was his assessments of how the Russians reasoned and reacted. No secret spying, just intelligent analysis based on experience.

One very important factor about Gordievsky’s contribution: The Brits never found a single lie or exaggeration in anything he told them. Early on, when he started giving them information, they had tested him by including questions to which they actually knew the answers from other sources. He was always truthful and had a very good memory. That is an important reason why I am convinced the conviction of Norwegian Arne Treholt, who spied for the Russians, was right: Treholt WAS guilty. There was info whose source was kept secret in the court case against Treholt in 1984/85, but it has later (after Gordievsky’s defection) been made public that this came from Gordievsky, who was then still in place as a KGB officer at the Soviet embassy in London and could not be compromised. He had had dealings with Treholt (probably in Copenhagen). There was other convincing evidence against Treholt also, but certainly information from Gordievsky is very high on my reliability scale.