Analysis: Al-Qaeda shifts strategic focus to Syria while still seeking to attack West

September 9, 2019 Leave a comment

In an effort to remain relevant, al-Qaeda has shifted its strategic focus from Yemen to Syria but continues to pursue a globalist agenda by seeking ways to attack Western targets, according to an expert report. Following the meteoric rise of the Islamic State in 2014, al-Qaeda found it difficult to retain its title as the main representative of the worldwide Sunni insurgency. But in an argue published last week on the website of the RAND Corporation, two al-Qaeda experts argue that the militant group is rebounding.

In an effort to remain relevant, al-Qaeda has shifted its strategic focus from Yemen to Syria but continues to pursue a globalist agenda by seeking ways to attack Western targets, according to an expert report. Following the meteoric rise of the Islamic State in 2014, al-Qaeda found it difficult to retain its title as the main representative of the worldwide Sunni insurgency. But in an argue published last week on the website of the RAND Corporation, two al-Qaeda experts argue that the militant group is rebounding.

The authors, Middle East Institute senior fellow Charles Listeris and RAND senior political scientist Colin Clarke, editorial that al-Qaeda followed a pragmatic and patient strategy after 2014. Specifically, the group remained on the margins and “deliberately let the Islamic State bear the brunt of the West’s counterterrorism campaign” they argue. At the same time, al-Qaeda has sought to remain relevant by shifting the center of its activity from Yemen to Syria. That decision appears to have been taken in 2014, when the group began to systematically transport assets and resources from its traditional strongholds of Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Levant, the authors argue.

Observers are still evaluating the implications of al-Qaeda’s strategic shift. Listeris and Clarke note that counterterrorism experts have yet to fully understand them. What appears certain is that al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria, the al-Nusra Front, “proved to be the most potent military actor on the battlefield” in the Levant. It did so by operating largely independently from al-Qaeda central, which allowed it to act with speed in pursuit of a strictly localized agenda that attracted many locals. At the same time, however, al-Nusra’s independence effectively separated it from its parent organization. Many al-Qaeda loyalists accused the group of abandoning al-Qaeda’s principles and left it when it rebranded itself to Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (Levantine Conquest Front) in 2016 and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (Organization for the Liberation of the Levant) in 2017.

Al-Qaeda itself denounced Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in 2018 and today supports a number of smaller militias that operate on the ground in Syria. These smaller groups appear to be extremely professional and experienced, and are staffed by “veterans with decades of experience at al Qaeda’s highest levels”. What does this mean about al-Qaeda’s strategic priorities? Listeris and Clarke argue that Syria remains al-Qaeda’s priority. But the group remains focused on attacking the West while also pursuing guerrilla warfare in Syria, they say. This reflects al-Qaeda’s overarching narrative, namely to fight in local conflicts while pursuing the “far enemy” (the West), which it sees as a mortal enemy of Islam.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 09 September 2019 | Permalink

Analysis: Assad’s collapse in Syria was a strategic surprise to Israel

December 20, 2024 by intelNews 7 Comments

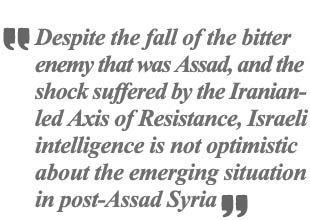

Israeli intelligence assessed that, despite the shocks it had suffered in recent months, the so-called Axis of Resistance against Israel —mainly Hezbollah, Syria, and Iran— was stable. A scenario of rapid collapse of the government in Syria had not been assessed as a possibility, or even given a low probability tag. That was primarily because the Assad family had governed Syria for almost 60 years.

Following the Assad regime’s collapse, the focus of Israel’s intelligence is on analyzing the intentions of the major rebel organization, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, and understanding how —if at all— it will lead the new administration in Syria. Israel is also examining developments in southern Syria, as well as what is happening at the Syrian and Russian military bases in Latakia and Tartus. Moreover, the IDF is monitoring the activities of Iranian elements in Syria, including on the border with Lebanon, to prevent the possibility of military equipment being transferred from Syria to Hezbollah.

southern Syria, as well as what is happening at the Syrian and Russian military bases in Latakia and Tartus. Moreover, the IDF is monitoring the activities of Iranian elements in Syria, including on the border with Lebanon, to prevent the possibility of military equipment being transferred from Syria to Hezbollah.

It is clear to Israel that Turkey stands behind the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham organization and that Ankara armed and supported the group for a significant period. What is less clear is whether and how Turkey’s involvement in Syria could threaten Israel’s interests, given that Israel’s relations with Turkey have deteriorated dramatically in recent years.

Assad was a key member of the pro-Iranian Axis of Resistance. Following his fall from power, Iran and Hezbollah could lose their main logistical hub for producing, transferring, and storing weapons, as well as training their forces and militias. Additionally, Syria under Assad constantly posed the threat of turning into yet another battlefront against Israel. Without Assad, Russia could lose its grip on Syria —the only country in the Middle East where Russian influence dominates that of the United States. The Russians could also lose access to their military bases in Syria, which offered the Russian Navy access to the waters of the Mediterranean.

Despite the fall of the bitter enemy that was Assad’s Syria, and the deep shock suffered by the Iranian-led Axis of Resistance camp that has been dominant in the Middle East in recent decades, Israeli intelligence is not optimistic about the emerging situation in post-Assad Syria. Syria is a collection of minorities —Druze, Kurds, Alawites, and Christians— that have been artificially joined together despite carrying bitter, bloody scores. The latter may erupt sharply, especially against the Alawites. Concepts such as liberal politics, civil society, or a cohesive nation-state, have never existed inside Syria.

It follows that Israel is very concerned about the emerging uncertainty in Syria. Immediately after the fall of Assad, the IDF strengthened its defenses on the Golan Heights border to ensure that the chaos in Syria did not spill over into Israel. Meanwhile, Israel is in contact —both directly and through intermediaries— with several Syrian rebel groups, including Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. The Israeli message at this stage is a demand that the rebels not approach the border, along with a warning that, if they violate the separation of forces agreement, Israel will respond with force.

And a final note: assessments in relation to the Syrian regime’s collapse continue to emerge in the IDF and the Israeli intelligence community. These assessments concern the extent to which the lessons of October 7 have been sufficiently analyzed and assimilated within Israel. Specifically, there are questions about whether this new intelligence surprise in Syria may stem from the fact that an in-depth investigation into the lessons of October 7 has yet to be carried out during the 14 months of the war with Hamas.

► Author: Avner Barnea* | Date: 20 December 2024 | Permalink

Dr. Avner Barnea is research fellow at the National Security Studies Center of the University of Haifa in Israel. He served as a senior officer in the Israel Security Agency (ISA). He is the author of We Never Expected That: A Comparative Study of Failures in National and Business Intelligence (Lexington Books, 2021).

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Analysis, Avner Barnea, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Iran, Israel, News, Syria, Turkey