Pro-Soviet radicals planned to kill Gorbachev in East Germany, book claims

September 11, 2018 Leave a comment

A group of German radicals planned to assassinate Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in East Germany in 1989, thus triggering a Soviet military invasion of the country, according to a new book written by a former British spy. The book is entitled Pilgrim Spy: My Secret War Against Putin, the KGB and the Stasi (Hodder & Stoughton publishers) and is written by “Tom Shore”, the nom de guerre of a former officer in the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). The book chronicles the work of its author, who claims that in 1989 he was sent by MI6 to operate inside communist East Germany without an official cover. That means that he was not a member of the British diplomatic community in East Germany and thus had no diplomatic immunity while engaging in espionage. His mission was to uncover details of what MI6 thought was a Soviet military operation against the West that would be launched from East Germany.

A group of German radicals planned to assassinate Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in East Germany in 1989, thus triggering a Soviet military invasion of the country, according to a new book written by a former British spy. The book is entitled Pilgrim Spy: My Secret War Against Putin, the KGB and the Stasi (Hodder & Stoughton publishers) and is written by “Tom Shore”, the nom de guerre of a former officer in the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). The book chronicles the work of its author, who claims that in 1989 he was sent by MI6 to operate inside communist East Germany without an official cover. That means that he was not a member of the British diplomatic community in East Germany and thus had no diplomatic immunity while engaging in espionage. His mission was to uncover details of what MI6 thought was a Soviet military operation against the West that would be launched from East Germany.

In his book, Shore says that he did not collect any actionable intelligence on the suspected Soviet military operation. He did, however, manage to develop sources from within the growing reform movement in East Germany. The leaders of that movement later spearheaded the widespread popular uprising that led to the collapse of the German Democratic Republic and its eventual unification with West Germany. While finding his way around the pro-democracy movement, Shore says that he discovered a number of self-described activists who had been planted there by the East German government or the Soviet secret services. Among them, he says, were members of the so-called Red Army Faction (RAF). Known also as the Baader Meinhoff Gang or the Baader-Meinhof Group, the RAF was a pro-Soviet guerrilla group that operated in several Western European countries, including Germany, Belgium and Holland. Its members participated in dozens of violent actions from 1971 to 1993, in which over 30 people were killed. Among other attacks, the group tried to kill the supreme allied commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and launched a sniper attack on the US embassy in Bonn. The group is known to have received material, logistical and operational support from a host of Eastern Bloc countries, including East Germany, Poland and Yugoslavia.

According to Shore, the RAF members who had infiltrated the East German reform movement were planning to assassinate Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev during his official visit to East Germany on October 7, 1989. The visit was planned to coincide with the 40th anniversary celebrations of the formation of the German Democratic Republic in 1949, following the collapse of the Third Reich. Shore says he discovered that the assassination plot had been sponsored by hardline members of the Soviet Politburo, the communist country’s highest policy-making body, and by senior officials of the KGB. The plan involved an all-out military takeover of East Germany by Warsaw Pact troops, similar to that of Czechoslovakia in 1968. But Shore claims that he was able to prevent the RAF’s plan with the assistance of members of the East German reform movement. He says, however, that at least two of the RAF members who planned to kill Gorbachev remain on the run to this day. The RAF was officially dissolved in 1998, when its leaders sent an official communiqué to the Reuters news agency announcing the immediate cessation of all RAF activities. However, three former RAF members remain at large. They are Ernst-Volker Staub, Burkhard Garweg and Daniela Klette, all of them German citizens, who are believed to be behind a series of bank robberies in Italy, Spain and France in recent years.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 11 September 2018 | Permalink

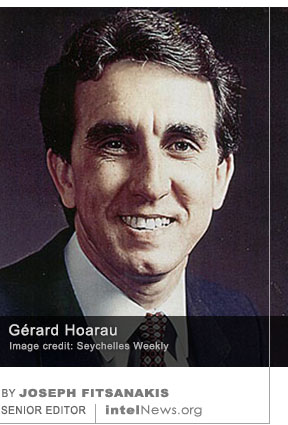

A man has been arrested by British counter-terrorism police in Northern Ireland, reportedly in connection with the assassination of a Seychelles exiled political leader in London in 1985. No-one has ever been charged with the murder of Gérard Hoarau, who was gunned down with a Sterling submachine gun in Edgware, London, on November 29, 1985. At the time of his killing, the 35-year-old Hoarau led the Mouvement Pour La Resistance (MPR), which was outlawed by the Seychelles government but was supported by Western governments and their allies in Africa. The reason was that the MPR challenged the president of the Seychelles, France-Albert René, leader of the leftwing Seychelles People’s United Party —known today as the Seychelles People’s United Party. The British-educated René assumed the presidency via a coup d’etat in 1977, which was supported by neighboring Tanzania, and remained in power in the island-country until 2004.

A man has been arrested by British counter-terrorism police in Northern Ireland, reportedly in connection with the assassination of a Seychelles exiled political leader in London in 1985. No-one has ever been charged with the murder of Gérard Hoarau, who was gunned down with a Sterling submachine gun in Edgware, London, on November 29, 1985. At the time of his killing, the 35-year-old Hoarau led the Mouvement Pour La Resistance (MPR), which was outlawed by the Seychelles government but was supported by Western governments and their allies in Africa. The reason was that the MPR challenged the president of the Seychelles, France-Albert René, leader of the leftwing Seychelles People’s United Party —known today as the Seychelles People’s United Party. The British-educated René assumed the presidency via a coup d’etat in 1977, which was supported by neighboring Tanzania, and remained in power in the island-country until 2004. The Prime Minister of Britain, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, was kept in the dark by his own home secretary about the discovery of a fourth member of the infamous Cambridge Spy Ring in 1964, according to newly released files. The Cambridge Spies were a group of British diplomats and intelligence officials who worked secretly for the Soviet Union from their student days in the 1930s until the 1960s. They included Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and H.A.R. “Kim” Philby, all of whom eventually defected to the Soviet Union. In 1964, Sir Anthony Blunt, an art history professor who in 1945 became Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and was knighted in 1954, admitted under interrogation by the British Security Service (MI5) that he had operated as the fourth member of the spy ring.

The Prime Minister of Britain, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, was kept in the dark by his own home secretary about the discovery of a fourth member of the infamous Cambridge Spy Ring in 1964, according to newly released files. The Cambridge Spies were a group of British diplomats and intelligence officials who worked secretly for the Soviet Union from their student days in the 1930s until the 1960s. They included Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and H.A.R. “Kim” Philby, all of whom eventually defected to the Soviet Union. In 1964, Sir Anthony Blunt, an art history professor who in 1945 became Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and was knighted in 1954, admitted under interrogation by the British Security Service (MI5) that he had operated as the fourth member of the spy ring. A newly declassified report by the Inspector General of the United States Central Intelligence Agency reveals that the South Vietnamese generals who overthrew President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963 used CIA money “to reward opposition military who joined the coup”. Acknowledging that “the passing of these funds is obviously a very sensitive matter”, the CIA Inspector General’s report contradicts the sworn testimony of Lucien E. Conein, the CIA liaison with the South Vietnamese generals. In 1975, Conein told a United States Senate committee that the agency funds, approximately $70,000 or 3 million piasters, were used for food, medical supplies, and “death benefits” for the families of South Vietnamese soldiers killed in the coup.

A newly declassified report by the Inspector General of the United States Central Intelligence Agency reveals that the South Vietnamese generals who overthrew President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963 used CIA money “to reward opposition military who joined the coup”. Acknowledging that “the passing of these funds is obviously a very sensitive matter”, the CIA Inspector General’s report contradicts the sworn testimony of Lucien E. Conein, the CIA liaison with the South Vietnamese generals. In 1975, Conein told a United States Senate committee that the agency funds, approximately $70,000 or 3 million piasters, were used for food, medical supplies, and “death benefits” for the families of South Vietnamese soldiers killed in the coup. Files released on Monday by the British government reveal new evidence about one of the most prolific Soviet spy rings that operated in the West after World War II, which became known as the Portland Spy Ring. Some of the members of the Portland Spy Ring were Soviet operatives who, at the time of their arrest, posed as citizens of third countries. All were non-official-cover intelligence officers, or NOCs, as they are known in Western intelligence parlance. Their Soviet —and nowadays Russian— equivalents are known as illegals. NOCs are high-level principal agents or officers of an intelligence agency, who operate without official connection to the authorities of the country that employs them. During much of the Cold War, NOCs posed as business executives, students, academics, journalists, or non-profit agency workers. Unlike official-cover officers, who are protected by diplomatic immunity, NOCs have no such protection. If arrested by authorities of their host country, they can be tried and convicted for engaging in espionage.

Files released on Monday by the British government reveal new evidence about one of the most prolific Soviet spy rings that operated in the West after World War II, which became known as the Portland Spy Ring. Some of the members of the Portland Spy Ring were Soviet operatives who, at the time of their arrest, posed as citizens of third countries. All were non-official-cover intelligence officers, or NOCs, as they are known in Western intelligence parlance. Their Soviet —and nowadays Russian— equivalents are known as illegals. NOCs are high-level principal agents or officers of an intelligence agency, who operate without official connection to the authorities of the country that employs them. During much of the Cold War, NOCs posed as business executives, students, academics, journalists, or non-profit agency workers. Unlike official-cover officers, who are protected by diplomatic immunity, NOCs have no such protection. If arrested by authorities of their host country, they can be tried and convicted for engaging in espionage. The United States Central Intelligence Agency believed that Yugoslavia was on the brink of becoming a nuclear-armed state in 1975, due partly to assistance from Washington, according to newly declassified documents. The documents, which date from 1957 to 1986, were

The United States Central Intelligence Agency believed that Yugoslavia was on the brink of becoming a nuclear-armed state in 1975, due partly to assistance from Washington, according to newly declassified documents. The documents, which date from 1957 to 1986, were  One of the Cold War’s most recognizable spy figures, George Blake, who escaped to the Soviet Union after betraying British intelligence, issued a rare statement last week, praising the successor agency to Soviet-era KGB. Blake was born George Behar in Rotterdam, Holland, to a Dutch mother and a British father. Having fought with the Dutch resistance against the Nazis, he escaped to Britain, where he joined the Secret Intelligence Service, known as MI6, in 1944. He was serving in a British diplomatic post in Korea in 1950, when he was captured by advancing North Korean troops and spent time in a prisoner of war camp. He was eventually freed, but, unbeknownst to MI6, had become a communist and come in contact with the Soviet KGB while in captivity. Blake remained in the service of the KGB as a defector-in-place until 1961, when he was arrested and tried for espionage.

One of the Cold War’s most recognizable spy figures, George Blake, who escaped to the Soviet Union after betraying British intelligence, issued a rare statement last week, praising the successor agency to Soviet-era KGB. Blake was born George Behar in Rotterdam, Holland, to a Dutch mother and a British father. Having fought with the Dutch resistance against the Nazis, he escaped to Britain, where he joined the Secret Intelligence Service, known as MI6, in 1944. He was serving in a British diplomatic post in Korea in 1950, when he was captured by advancing North Korean troops and spent time in a prisoner of war camp. He was eventually freed, but, unbeknownst to MI6, had become a communist and come in contact with the Soviet KGB while in captivity. Blake remained in the service of the KGB as a defector-in-place until 1961, when he was arrested and tried for espionage. The life of Kim Philby, one of the Cold War’s most recognizable espionage figures, is the subject of a new exhibition that opened last week in Moscow. Items displayed at the exhibition include secret documents stolen by Philby and passed to his Soviet handlers during his three decades in the service of Soviet intelligence. While working as a senior member of British intelligence, Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as ‘Kim’ to his friends, spied on behalf of the Soviet NKVD and KGB. His espionage lasted from about 1933 until 1963, when he secretly defected to the USSR from his home in Beirut, Lebanon. Philby’s defection sent ripples of shock across Western intelligence and is often seen as one of the most dramatic incidents of the Cold War.

The life of Kim Philby, one of the Cold War’s most recognizable espionage figures, is the subject of a new exhibition that opened last week in Moscow. Items displayed at the exhibition include secret documents stolen by Philby and passed to his Soviet handlers during his three decades in the service of Soviet intelligence. While working as a senior member of British intelligence, Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as ‘Kim’ to his friends, spied on behalf of the Soviet NKVD and KGB. His espionage lasted from about 1933 until 1963, when he secretly defected to the USSR from his home in Beirut, Lebanon. Philby’s defection sent ripples of shock across Western intelligence and is often seen as one of the most dramatic incidents of the Cold War. The role of the CIA in funding and helping to organize anti-Soviet groups inside the USSR has been known for decades. But, as intelNews explained in

The role of the CIA in funding and helping to organize anti-Soviet groups inside the USSR has been known for decades. But, as intelNews explained in  Recently declassified documents from the archive of the Central Intelligence Agency detail financial and material support given by the United States to groups of armed guerrillas in Soviet Latvia in the 1950s. The documents, initially marked ‘Top Secret’ but now declassified, show that the CIA was aware and supported the activities of an anti-Soviet guerrilla army known as ‘the Forest Brothers’. Known also as ‘the Forest Brethren’, the group was formed in the Baltic States in 1944, as the Soviet Red Army established Soviet control over the previously German-occupied states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The Soviet Union had previously occupied and annexed the three Baltic countries, in a failed attempt to pre-empt Germany’s eastward military expansion. Groups like the Forest Brothers consisted of the most militant members of anti-Soviet groups in the Baltic States, many of whom were ideologically opposed to Soviet Communism.

Recently declassified documents from the archive of the Central Intelligence Agency detail financial and material support given by the United States to groups of armed guerrillas in Soviet Latvia in the 1950s. The documents, initially marked ‘Top Secret’ but now declassified, show that the CIA was aware and supported the activities of an anti-Soviet guerrilla army known as ‘the Forest Brothers’. Known also as ‘the Forest Brethren’, the group was formed in the Baltic States in 1944, as the Soviet Red Army established Soviet control over the previously German-occupied states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The Soviet Union had previously occupied and annexed the three Baltic countries, in a failed attempt to pre-empt Germany’s eastward military expansion. Groups like the Forest Brothers consisted of the most militant members of anti-Soviet groups in the Baltic States, many of whom were ideologically opposed to Soviet Communism. State-sponsored industrial espionage aimed at stealing foreign technical secrets may boost a country’s technological sector in the short run, but ultimately stifles it, according to the first study on the subject. The study is based on over 150,000 declassified documents belonging to the East German Ministry for State Security, known as Stasi. The now-defunct intelligence agency of communist-era East Germany was known for its extensive networks of informants, which focused intensely on acquiring technical secrets from abroad.

State-sponsored industrial espionage aimed at stealing foreign technical secrets may boost a country’s technological sector in the short run, but ultimately stifles it, according to the first study on the subject. The study is based on over 150,000 declassified documents belonging to the East German Ministry for State Security, known as Stasi. The now-defunct intelligence agency of communist-era East Germany was known for its extensive networks of informants, which focused intensely on acquiring technical secrets from abroad. General Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov, who held senior positions in the Soviet KGB for 35 years, and handled a global network of Soviet undercover officers from 1979 until 1991,

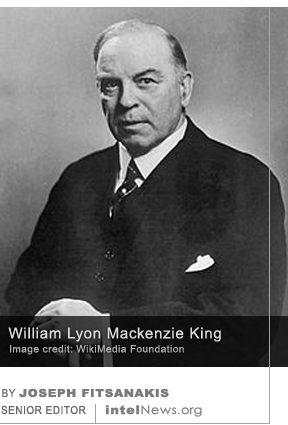

General Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov, who held senior positions in the Soviet KGB for 35 years, and handled a global network of Soviet undercover officers from 1979 until 1991,  Canadian officials speculated that Soviet spies stole a missing volume from the private diary collection of William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada’s longest-serving prime minister, who led the country in the run-up to the Cold War. A liberal anticommunist, Mackenzie King was Canada’s prime minister from 1925 to 1948, with a break from 1930 to 1935. He is known for having led the establishment of Canada’s welfare state along Western European standards.

Canadian officials speculated that Soviet spies stole a missing volume from the private diary collection of William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada’s longest-serving prime minister, who led the country in the run-up to the Cold War. A liberal anticommunist, Mackenzie King was Canada’s prime minister from 1925 to 1948, with a break from 1930 to 1935. He is known for having led the establishment of Canada’s welfare state along Western European standards. Werner Stiller, also known as Klaus-Peter Fischer, whose spectacular defection to the West in 1979 inflicted one of the Cold War’s most serious blows to the intelligence agency of East Germany, has died in Hungary. Stiller, 69, is believed to have died on December 20 of last year, but his death was not

Werner Stiller, also known as Klaus-Peter Fischer, whose spectacular defection to the West in 1979 inflicted one of the Cold War’s most serious blows to the intelligence agency of East Germany, has died in Hungary. Stiller, 69, is believed to have died on December 20 of last year, but his death was not

Book alleges 1980s British Labour Party leader was Soviet agent

September 21, 2018 by Joseph Fitsanakis 1 Comment

Two years later, in 1985, Oleg Gordievsky, a colonel in the Soviet KGB, defected to Britain and disclosed that he had been a double spy for the British from 1974 until his defection. In 1995, Gordievsky chronicled his years as a KGB officer and his espionage for Britain in a memoir, entitled Next Stop Execution. The book was abridged and serialized in the London-based Times newspaper. In it, Gordievsky claimed that Foot had been a Soviet “agent of influence” and was codenamed “Agent BOOT” by the KGB. Foot proceeded to sue The Times for libel, after the paper published a leading article headlined “KGB: Michael Foot was our agent”. The Labour Party politician won the lawsuit and was awarded financial restitution from the paper.

This past week, however, the allegations about Foot’s connections with Soviet intelligence resurfaced with the publication of The Spy and the Traitor, a new book chronicling the life and exploits of Gordievsky. In the book, Times columnist and author Ben Macintyre alleges that Gordievsky’s 1995 allegations about Foot were accurate and that Gordievsky passed them on to British intelligence before openly defecting to Britain. According to Macintyre, Gordievsky briefed Baron Armstrong of Ilminster, a senior civil servant and cabinet secretary to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Lord Armstrong, a well-connected veteran of British politics, in turn communicated the information to the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) in the summer of 1982, says Macintyre. The Times columnist alleges that MI6 received specific information from Lord Armstrong, according to which Foot had been in contact with the KGB for years and that he had been paid the equivalent of £37,000 ($49,000) in today’s money for his services. The spy agency eventually determined that Foot may not himself have been conscious that the Soviets were using him as an agent of influence. But MI6 officials viewed Gordievsky’s allegations significant enough to justify a warning given to Queen Elizabeth II, in case the Labour Party won the 1983 general election and Foot became Britain’s prime minister.

The latest allegations prompted a barrage of strong condemnations from current and former officials of the Labour Party. Its current leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who like Foot also comes from the left of the Party, denounced Macintyre for “smearing a dead man, who successfully defended himself [against the same allegations] when he was alive”. Labour’s deputy leader, John McDonnell, criticized The Times for “debasing [the] standards of journalism in this country. They used to be called the gutter press. Now they inhabit the sewers”, he said. Neil Kinnock, who succeeded Foot in the leadership of the Labour Party in 1983, said Macintyre’s allegations were “filthy” and described Foot as a “passionate and continual critic of the Soviet Union”.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 21 September 2018 | Permalink

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Agent BOOT, Ben Macintyre, book news and reviews, Cold War, history, KGB, Labour Party (UK), Michael Foot, News, Oleg Gordievsky, UK, USSR