Revealed: Letters between Margaret Thatcher and KGB defector

January 2, 2015 Leave a comment

By IAN ALLEN | intelNews.org

By IAN ALLEN | intelNews.org

Files released this week have revealed part of the personal correspondence between the late British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and one of the Cold War’s most important Soviet spy defectors. Oleg Gordievsky entered the Soviet KGB in 1963. He soon joined the organization’s Second Directorate, which was responsible for coordinating the activities of Soviet ‘illegals’, that is, intelligence officers operating abroad without official diplomatic cover. Gordievsky’s faith in the Soviet system was irreparably damaged in 1968, when Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia. In 1974, while stationed in Danish capital Copenhagen, he made contact with British intelligence and began his career as a double agent for the United Kingdom. In 1985, shortly before he was to assume the post of KGB station chief at the Soviet embassy in London, he was summoned back to Moscow by an increasingly suspicious KGB. He was aggressively interrogated but managed to make contact with British intelligence and was eventually smuggled out of Russia via Finland, riding in the trunk of a British diplomatic vehicle. His defection was announced a few days later by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who had personally approved his exfiltration from the USSR. Files released this week by the British National Archives show that the British Prime Minister took a personal interest in Gordievsky’s wellbeing following his exfiltration, and even corresponded with him after the Soviet defector personally wrote to her to ask for her intervention to help him reunite with his wife Leila and two daughters, who remained in the Soviet Union. In his letter, written in 1985, Gordievsky told Thatcher that his life had “no meaning” unless he was able to be with his family. On September 7, 1985, the British Prime Minister responded with a letter to the Soviet defector, urging him not to give up. “Please do not say that life has no meaning”, she wrote. “There is always hope. And we shall do all to help you through these difficult days”. She added that the two should meet once the “immediate situation” of the worldwide media attention caused by his exfiltration subsided. Thatcher went on to publicly urge for Moscow to allow Gordievsky’s family to reunite with the Soviet defector, “on humanitarian grounds”. But it was in 1991, after the collapse of communism in the USSR, when Gordievsky’s family was finally able to join him in the UK.

Swedish double spy who escaped to Moscow in 1987 dies at 77

February 9, 2015 by Ian Allen 3 Comments

Sweden’s most notorious Cold-War spy, who went on the run for nearly a decade after managing to escape from prison in 1987, has died in Stockholm. Born in the Swedish capital in 1937, Stig Eugén Bergling became a police officer in the late 1950s prior to joining SÄPO, the Swedish Security Service, in 1967. He initially worked in the Service’s surveillance unit, and later joined several counterintelligence operations, mostly against Soviet and East European intelligence services. In 1979, while posted by SÄPO in Tel Aviv, he was arrested by the Israelis for selling classified documents to the GRU, the military intelligence agency of the USSR.

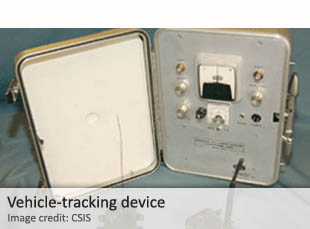

He was promptly extradited to Sweden, where he stood trial for espionage and treason. His trial captivated the headlines, as details about the spy tradecraft he employed while spying for the Soviets, including radio transmitters, invisible ink and microdots, were revealed in court. He said in his testimony that he sold over 15,000 classified Swedish government documents to the Soviets, not due to any ideological allegiance with the Kremlin, but simply in order to make money. Bergling was sentenced to life in prison, while lawyers for the prosecution argued in court that the reorganization of Sweden’s defense and intelligence apparatus, which had been caused by Bergling’s espionage, would cost the taxpayer in excess of $45 million. For the next six years, the convicted spy disappeared from the headlines, after legally changing his name to Eugen Sandberg while serving his sentence.

But in 1987, during a conjugal visit to his wife, he escaped with her using several rented cars, eventually making it to Finland. When they arrived in Helsinki, Bergling contacted the Soviet embassy, which smuggled him and his wife across to the USSR. The couple’s escape caused a major stir in Sweden, and an international manhunt was initiated for their capture. In 1994, the two fugitives suddenly returned to Sweden from Lebanon, where they had been living, claiming they were homesick and missed their families. They said they had lived in Moscow and Budapest under the aliases of Ivar and Elisabeth Straus. Bergling was sent back to prison, while his wife was not sentenced due to ill health. She died of cancer in 1997. Bergling changed his name again, this time to Sydholt, and lived his final years in a nursing home in Stockholm until his recent death. He was 77.

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Cold War, defectors, double agents, Eugen Sandberg, Eugen Sydholt, GRU, history, obituaries, SAPO (Sweden), Stig Bergling, Sweden