Research sheds light on Japan’s wartime espionage network inside the United States

September 26, 2022 1 Comment

MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN about the wartime intelligence exploits of the Allies against Japan. Such exploits range from the United States’ success in breaking the Japanese JN-25 naval code, to the extensive operations of the Soviet Union’s military intelligence networks in Tokyo. In contrast, very little is known about Japan’s intelligence performance against the Allies in the interwar years, as well as after 1941. Now a new paper by an international team or researchers sheds light on this little-studied aspect of intelligence history.

MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN about the wartime intelligence exploits of the Allies against Japan. Such exploits range from the United States’ success in breaking the Japanese JN-25 naval code, to the extensive operations of the Soviet Union’s military intelligence networks in Tokyo. In contrast, very little is known about Japan’s intelligence performance against the Allies in the interwar years, as well as after 1941. Now a new paper by an international team or researchers sheds light on this little-studied aspect of intelligence history.

The researchers, Ron Drabkin, visiting scholar at the University of Notre Dame, K. Kusunoki, of the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force, and Bradley W. Hart, associate professor at California State University, Fresno, published their work on September 22 in the peer-reviewed journal Intelligence and National Security. Their well-written article is entitled “Agents,  Attachés, and Intelligence Failures: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Efforts to Establish Espionage Networks in the United States Before Pearl Harbor”.

Attachés, and Intelligence Failures: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Efforts to Establish Espionage Networks in the United States Before Pearl Harbor”.

The authors acknowledge that the history of the intelligence efforts of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) has received very little attention by scholars. Consequently, it remains unexplored even in Japan, let alone in the international scholarship on intelligence. There are two main reasons for that. To begin with, the IJN systematically destroyed its intelligence files in the months leading to Japan’s official surrender in 1945. Then, following the war, fearing being implicated in war crimes trials, few of its undercover operatives voluntarily revealed their prior involvement in intelligence work.

Luckily, however, the past decade has seen the declassification of a number of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counterintelligence files relating to Japanese intelligence operations targeting the United States. Most of these files date from the 1930s and early 1940s. Additionally, a number of related documents have been declassified by the government of Mexico, which is important, given that Mexico was a major base for Japanese intelligence operations targeting the United States. Read more of this post

Nearly 2,000 missing British intelligence files relating to the so-called Munich Agreement, a failed attempt by Britain, France and Italy to appease Adolf Hitler in 1938, may not have been destroyed, according to historians. On September 30, 1938, the leaders of France, Britain and Italy signed a peace treaty with the Nazi government of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The treaty, which became known as the Munich Agreement, gave Hitler de facto control of Czechoslovakia’s German-speaking areas, in return for him promising to resign from territorial claims against other countries, such as Poland and Hungary. Hours after the treaty was formalized, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arrived by airplane at an airport near London, and boldly proclaimed that he had secured “peace for our time” (pictured above). Contrary to Chamberlain’s expectations, however, the German government was emboldened by what it saw as attempts to appease it, and promptly proceeded to invade Poland, thus firing the opening shots of World War II in Europe.

Nearly 2,000 missing British intelligence files relating to the so-called Munich Agreement, a failed attempt by Britain, France and Italy to appease Adolf Hitler in 1938, may not have been destroyed, according to historians. On September 30, 1938, the leaders of France, Britain and Italy signed a peace treaty with the Nazi government of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The treaty, which became known as the Munich Agreement, gave Hitler de facto control of Czechoslovakia’s German-speaking areas, in return for him promising to resign from territorial claims against other countries, such as Poland and Hungary. Hours after the treaty was formalized, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arrived by airplane at an airport near London, and boldly proclaimed that he had secured “peace for our time” (pictured above). Contrary to Chamberlain’s expectations, however, the German government was emboldened by what it saw as attempts to appease it, and promptly proceeded to invade Poland, thus firing the opening shots of World War II in Europe. Japan has released secret documents from 1942 relating to the Tokyo spy ring led by Richard Sorge, a German who spied for the USSR and is often credited with helping Moscow win World War II. The documents detail efforts by the wartime Japanese government to trivialize the discovery of the

Japan has released secret documents from 1942 relating to the Tokyo spy ring led by Richard Sorge, a German who spied for the USSR and is often credited with helping Moscow win World War II. The documents detail efforts by the wartime Japanese government to trivialize the discovery of the  The daughter of Heinrich Himmler, who was second in command in the German Nazi Party until the end of World War II, worked for West German intelligence in the 1960s, it has been confirmed. Gudrun Burwitz was born Gudrun Himmler in 1929. During the reign of Adolf Hitler, her father, Heinrich Himmler, commanded the feared Schutzstaffel, known more commonly as the SS. Under his command, the SS played a central part in administering the Holocaust, and carried out a systematic campaign of extermination of millions of civilians in Nazi-occupied Europe. But the Nazi regime collapsed under the weight of the Allied military advance, and on May 20, 1945, Himmler was captured alive by Soviet troops. Shortly thereafter he was transferred to a British-administered prison, where, just days later, he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule that he had with him. Gudrun, who by that time was nearly 16 years old, managed to escape to Italy with her mother, where she was captured by American forces. She testified in the Nuremberg Trials and was eventually released in 1948. She settled with her mother in northern West Germany and lived away from the limelight of publicity until her death on May 24 of this year, aged 88.

The daughter of Heinrich Himmler, who was second in command in the German Nazi Party until the end of World War II, worked for West German intelligence in the 1960s, it has been confirmed. Gudrun Burwitz was born Gudrun Himmler in 1929. During the reign of Adolf Hitler, her father, Heinrich Himmler, commanded the feared Schutzstaffel, known more commonly as the SS. Under his command, the SS played a central part in administering the Holocaust, and carried out a systematic campaign of extermination of millions of civilians in Nazi-occupied Europe. But the Nazi regime collapsed under the weight of the Allied military advance, and on May 20, 1945, Himmler was captured alive by Soviet troops. Shortly thereafter he was transferred to a British-administered prison, where, just days later, he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule that he had with him. Gudrun, who by that time was nearly 16 years old, managed to escape to Italy with her mother, where she was captured by American forces. She testified in the Nuremberg Trials and was eventually released in 1948. She settled with her mother in northern West Germany and lived away from the limelight of publicity until her death on May 24 of this year, aged 88. The unmarked grave of a Dutch-born Nazi spy, who killed himself after spending several months working undercover in wartime Britain, will be marked with a headstone, 76 years after his death by suicide. Born in 1914 in The Hague, Holland, Englebertus Fukken joined the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, the Dutch affiliate of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party led by Adolf Hitler, in 1933. In 1940, shortly after the German invasion of Holland, Fukken, who had been trained as a journalist, was recruited by the Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence. Abwehr’s leadership decided to include Fukken in the ranks of undercover agents sent to Britain in preparation for Operation SEA LION, Germany’s plan to invade Britain.

The unmarked grave of a Dutch-born Nazi spy, who killed himself after spending several months working undercover in wartime Britain, will be marked with a headstone, 76 years after his death by suicide. Born in 1914 in The Hague, Holland, Englebertus Fukken joined the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, the Dutch affiliate of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party led by Adolf Hitler, in 1933. In 1940, shortly after the German invasion of Holland, Fukken, who had been trained as a journalist, was recruited by the Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence. Abwehr’s leadership decided to include Fukken in the ranks of undercover agents sent to Britain in preparation for Operation SEA LION, Germany’s plan to invade Britain. The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto.

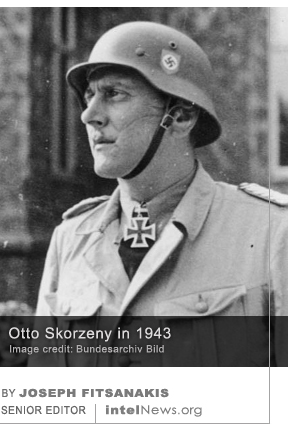

The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto. A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government.

A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government. A congratulatory letter sent by a senior Nazi official to

A congratulatory letter sent by a senior Nazi official to