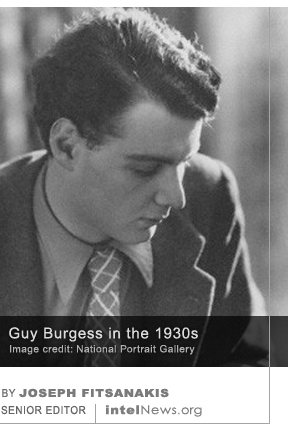

Cambridge spy’s last years in Russia are detailed in new biography

September 4, 2015 Leave a comment

The life of Guy Burgess, one of the so-called ‘Cambridge Five’ double agents, who spied on Britain for the Soviet Union before defecting to Moscow in 1951, is detailed in a new biography of the spy, written by Andrew Lownie. Like his fellow spies Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, Burgess was recruited by the Soviets when he was a student at Cambridge University. He shook the British intelligence establishment to its very core when he defected to the USSR along with Maclean, after the two felt that they were being suspected of spying for the Soviets.

The life of Guy Burgess, one of the so-called ‘Cambridge Five’ double agents, who spied on Britain for the Soviet Union before defecting to Moscow in 1951, is detailed in a new biography of the spy, written by Andrew Lownie. Like his fellow spies Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, Burgess was recruited by the Soviets when he was a student at Cambridge University. He shook the British intelligence establishment to its very core when he defected to the USSR along with Maclean, after the two felt that they were being suspected of spying for the Soviets.

A few years after his defection, Burgess wrote to a close friend back in the UK: “I am really […] very well and things are going much better for me here than I ever expected. I’m very glad I came”. However, in his book, entitled Stalin’s Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess, Lownie suggests that Burgess’ life in the USSR was far from ideal. After being welcomed by the Soviets as a hero, the Cambridge University graduate was transported to the isolated Siberian city of Kuybyshev. He lived for several months in a ‘grinder’, a safe house belonging to Soviet intelligence, where he was debriefed and frequently interrogated until his Soviet handlers were convinced that has indeed a genuine defector.

It was many years later that Burgess was able to leave Kuybyshev for Moscow, under a new name, Jim Andreyevitch Eliot, which had been given to him by the KGB. Initially he lived in a dacha outside Moscow, but was moved to the city in 1955, after he and Maclean spoke publicly about their defection from Britain. He was often visited in his one-bedroom apartment by Yuri Modin, his Soviet intelligence handler back in the UK. According to Lownie, Burgess often complained to Modin about the way he was being treated by the Soviet authorities. His apartment had apparently been bugged by the KGB, and he was constantly followed each time he stepped outside.

The British defector worked for a Soviet publishing house and produced foreign-policy analyses for the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He also produced a training manual for KGB officers about British culture and the British way of life. But he did not like living in the USSR and argued that he should be allowed to return to the UK, insisting that he could successfully defend himself if interrogated by British counterintelligence. Eventually, Burgess came to the realization that he would never return to his home country. He became depressed, telling friends that he “did not want to die in Russia”. But in the summer of 1963 he was taken to hospital, where he eventually died from acute liver failure caused by his excessive drinking.

Andrew Lownie’s Stalin’s Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess, is published by Hodder & Stoughton in the UK and by St Martins’ Press in the US. It is scheduled to come out in both countries on September 10.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 04 September 2015 | Permalink

Russian security services honor members of the Cambridge spy ring with plaque

December 23, 2019 by Joseph Fitsanakis Leave a comment

In 1951, shortly before they were detained by British authorities on suspicion of espionage, Burgess and Maclean defected to the Soviet Union. They both lived there under new identities and, according to official histories, as staunch supporters of Soviet communism. Some biographers, however, have suggested that the two Englishmen grew disillusioned with communism while living in the Soviet Union, and were never truly trusted by the authorities Moscow. When they died, however, in 1963 (Burgess) and 1983 (Maclean), the Soviet intelligence services celebrated them as heroes.

On Friday, the Soviet state recognized the two defectors in an official ceremony in the Siberian city of Samara, where they lived for a number of years, until the authorities relocated them to Moscow. Kuibyshev, as the city was known during Soviet times, was technically a vast classified facility where much of the research for the country’s space program took place. While in Kuibyshev, Burgess and Maclean stayed at a Soviet intelligence ‘safe house’, where they were debriefed and frequently interrogated, until their handlers were convinced that they were indeed genuine defectors.

At Friday’s ceremony, officials unveiled a memorial plaque at the entrance to the building where Burgess and Maclean lived. According to the Reuters news agency, the plaque reads: “In this building, from 1952-1955, lived Soviet intelligence officers, members of the ‘Cambridge Five’, Guy Francis Burgess and Donald Maclean”. On the same day, a letter written by Sergei Naryshkin, head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), one of the institutional descendants of the Soviet-era KGB, appeared online. In the letter, Naryshkin said that Burgess and Maclean had made “a significant contribution to the victory over fascism [during World War II], the protection of [the USSR’s] strategic interests, and ensuring the safety” of the Soviet Union and Russia.

Last year, Russian officials named a busy intersection in Moscow after Harold Adrian Russell Philby. Known as ‘Kim’ to his friends, Philby was a leading member of the Cambridge spies. He followed Burgess and Maclean to the USSR in 1963, where he defected after a long career with the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6).

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 22 December 2019 | Permalink

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Cambridge Five, Cold War, defectors, Donald Maclean, espionage, Guy Burgess, history, News, SVR (Russia), UK, USSR