North Korean radio station known for sending coded messages to spies goes silent

January 15, 2024 2 Comments

NORTH KOREA APPEARS TO have suspended a long-standing radio station, known for broadcasting content targeted at South Koreans, which also aired encrypted messages intended for North Korean spies abroad. Radio Pyongyang was founded by Korean communist forces in the 1940s. In 1950 it formed part of the North Korean state’s official media propaganda arm.

NORTH KOREA APPEARS TO have suspended a long-standing radio station, known for broadcasting content targeted at South Koreans, which also aired encrypted messages intended for North Korean spies abroad. Radio Pyongyang was founded by Korean communist forces in the 1940s. In 1950 it formed part of the North Korean state’s official media propaganda arm.

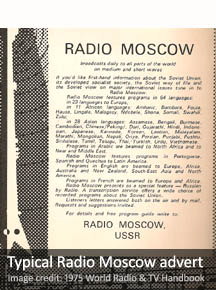

Throughout the Cold War, Radio Pyongyang aired hundreds of hours of news and cultural content every week. The broadcasts were in various languages and were exclusively aimed at international listeners. However, most of the station’s output was targeted at South Koreans. In 2002, the station was renamed Voice of Korea. Around that time, possibly owing to a temporary rapprochement between North and South Korea, the station curtailed much of its political programming. However, broadcasts featuring political content were resumed in 2016, as relations between the two warring sides began to deteriorate once again.

For much of its existence, the Voice of Korea has also been known to operate as a so-called numbers station. The term denotes shortwave radio stations, usually sponsored by a government entity, that regularly air broadcasts consisting of formatted number sequences. These sequences are widely believed to be encrypted communications addressed to intelligence officers operating abroad. They contain operational instructions and other directives that are typically undecipherable without the use of an encryption protocol. These stations also broadcast certain types of music, which function as codewords and are believed to signal specific directives to spies.

But the Voice of Korea unexpectedly fell silent last week. Its website, which features content in several languages, also appears to have been taken down. The sudden changes occurred days after North Korea’s Supreme Leader, Kim Jong-un, delivered a key address during the year-end plenum of the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) in Pyongyang, on December 31. In his speech, which became public on January 6, the North Korean leader declared that the reunification of Korea under communist principles —a longstanding goal of the WPK—had been rendered “impossible” due to widening differences in approach between the two Koreas.

The North Korean strongman also called for “a fundamental change” in the WPK’s policy on inter-Korean affairs. Finally, he discussed a series of steps for the “reorganization of entities” that govern North Korea’s relations with South Korea. Several North Korean government websites focusing on the reunification of Korea, including the Voice of Korea website, have since been taken down. North Korea observers suggest that the daily radio broadcasts of the Voice of Korea appear to be part of the reorganization declared by Kim Jong-UN on December 31.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 15 January 2024 | Permalink

In a development that is reminiscent of the Cold War, a radio station in North Korea appears to have resumed broadcasts of encrypted messages that are typically used to give instructions to spies stationed abroad. The station in question is the Voice of Korea, known in past years as Radio Pyongyang. It is operated by the North Korean government and airs daily programming consisting of music, current affairs and instructional propaganda in various languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French, English, and Russian. Last week however, the station interrupted its normal programming to air a series of numbers that were clearly intended to be decoded by a few select listeners abroad.

In a development that is reminiscent of the Cold War, a radio station in North Korea appears to have resumed broadcasts of encrypted messages that are typically used to give instructions to spies stationed abroad. The station in question is the Voice of Korea, known in past years as Radio Pyongyang. It is operated by the North Korean government and airs daily programming consisting of music, current affairs and instructional propaganda in various languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French, English, and Russian. Last week however, the station interrupted its normal programming to air a series of numbers that were clearly intended to be decoded by a few select listeners abroad.