Vienna’s wartime Gestapo chief worked for West German intelligence, records show

April 7, 2021 1 Comment

THE HEAD OF THE secret police in Nazi-occupied Vienna, who oversaw the mass deportation of Austrian Jews to concentration camps, worked for West Germany’s postwar spy agency, according to newly released records. Starting his career as a police officer in Munich during the Weimar Republic, Franz Josef Huber joined the Nazi Party in 1937. Due to his prior law enforcement work, he was immediately appointed to the office of Heinrich Müller, who headed the Gestapo —Nazi Germany’s secret police.

Following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, the Nazi Party sent Huber to Vienna, where he oversaw all criminal and political investigations by the Gestapo. He remained head of the Nazi secret police in the Austrian capital until December of 1944. Under his leadership, the Vienna branch of the Gestapo became one of the agency’s largest field offices, second only to its headquarters in Berlin, with nearly 1000 staff members. Huber himself was in regular communication with Adolf Eichmann, who was the logistical architect of the Holocaust. Nearly 66,000 Austrian Jews, most of them residents of Vienna, perished in German-run concentration camps under Huber’s watch.

In May of 1945, following the capitulation of Germany, Huber surrendered to American forces and was kept in detention for nearly four years. During his trial in the German city of Nuremburg, Huber admitted to having visited German-run concentration camps throughout his tenure in the Gestapo. But he claimed that he had not noticed signs of mistreatment of prisoners. He was eventually cleared of all charges against him and released in 1949, allegedly because allied forces wanted to concentrate on more senior members of the Nazi Party, including Huber’s boss, Heinrich Müller.

Last week, German public-service broadcaster ARD said it found Huber’s name in records belonging to the Federal Intelligence Service —Germany’s external intelligence agency. It turns out that, following his release from detention in 1948, Huber joined the Gehlen Organization —named after the first director of the BND, Reinhard Gehlen. Gehlen was a former general and military intelligence officer in the Nazi Wehrmacht, who had considerable experience in anti-Soviet and anti-communist operations. In 1956, as the Cold War was intensifying, the United States Central Intelligence Agency, which acted as the BND’s patron, appointed Gehlen as head of the BND, a post which he held until 1968. During his tenure, Gehlen staffed the BND with numerous Nazi war criminals, who had considerable expertise on the Soviet Union and anti-communism.

According to the ARD, Huber worked for the BND under Gehlen until 1967, when he retired along with other former Nazi BND officers. His retirement occurred at a time when the BND, under popular pressure, tried to cut ties with some of the most notorious former Nazis in its ranks. However, Huber was given a state pension, which he kept until his death in 1975. Following his retirement from the BND, he allegedly worked for an office equipment supplier in his hometown of Munich, without ever facing any prosecution for his wartime role in the Gestapo. In an article published on Monday, The New York Times claimed that the United States government was fully aware of Huber’s Nazi past.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 07 April 2021 | Permalink

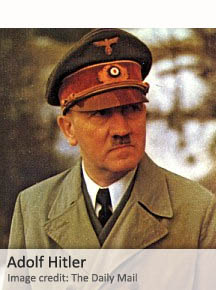

Nearly 2,000 missing British intelligence files relating to the so-called Munich Agreement, a failed attempt by Britain, France and Italy to appease Adolf Hitler in 1938, may not have been destroyed, according to historians. On September 30, 1938, the leaders of France, Britain and Italy signed a peace treaty with the Nazi government of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The treaty, which became known as the Munich Agreement, gave Hitler de facto control of Czechoslovakia’s German-speaking areas, in return for him promising to resign from territorial claims against other countries, such as Poland and Hungary. Hours after the treaty was formalized, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arrived by airplane at an airport near London, and boldly proclaimed that he had secured “peace for our time” (pictured above). Contrary to Chamberlain’s expectations, however, the German government was emboldened by what it saw as attempts to appease it, and promptly proceeded to invade Poland, thus firing the opening shots of World War II in Europe.

Nearly 2,000 missing British intelligence files relating to the so-called Munich Agreement, a failed attempt by Britain, France and Italy to appease Adolf Hitler in 1938, may not have been destroyed, according to historians. On September 30, 1938, the leaders of France, Britain and Italy signed a peace treaty with the Nazi government of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The treaty, which became known as the Munich Agreement, gave Hitler de facto control of Czechoslovakia’s German-speaking areas, in return for him promising to resign from territorial claims against other countries, such as Poland and Hungary. Hours after the treaty was formalized, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arrived by airplane at an airport near London, and boldly proclaimed that he had secured “peace for our time” (pictured above). Contrary to Chamberlain’s expectations, however, the German government was emboldened by what it saw as attempts to appease it, and promptly proceeded to invade Poland, thus firing the opening shots of World War II in Europe. Japan has released secret documents from 1942 relating to the Tokyo spy ring led by Richard Sorge, a German who spied for the USSR and is often credited with helping Moscow win World War II. The documents detail efforts by the wartime Japanese government to trivialize the discovery of the

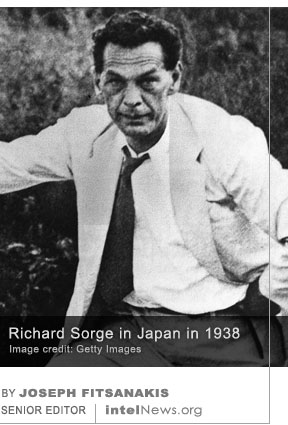

Japan has released secret documents from 1942 relating to the Tokyo spy ring led by Richard Sorge, a German who spied for the USSR and is often credited with helping Moscow win World War II. The documents detail efforts by the wartime Japanese government to trivialize the discovery of the  The daughter of Heinrich Himmler, who was second in command in the German Nazi Party until the end of World War II, worked for West German intelligence in the 1960s, it has been confirmed. Gudrun Burwitz was born Gudrun Himmler in 1929. During the reign of Adolf Hitler, her father, Heinrich Himmler, commanded the feared Schutzstaffel, known more commonly as the SS. Under his command, the SS played a central part in administering the Holocaust, and carried out a systematic campaign of extermination of millions of civilians in Nazi-occupied Europe. But the Nazi regime collapsed under the weight of the Allied military advance, and on May 20, 1945, Himmler was captured alive by Soviet troops. Shortly thereafter he was transferred to a British-administered prison, where, just days later, he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule that he had with him. Gudrun, who by that time was nearly 16 years old, managed to escape to Italy with her mother, where she was captured by American forces. She testified in the Nuremberg Trials and was eventually released in 1948. She settled with her mother in northern West Germany and lived away from the limelight of publicity until her death on May 24 of this year, aged 88.

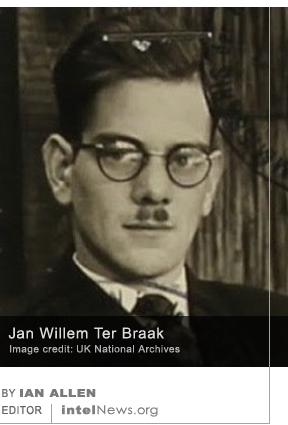

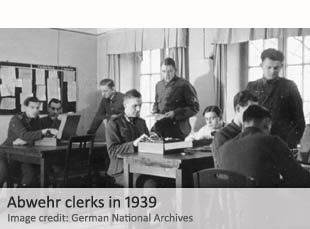

The daughter of Heinrich Himmler, who was second in command in the German Nazi Party until the end of World War II, worked for West German intelligence in the 1960s, it has been confirmed. Gudrun Burwitz was born Gudrun Himmler in 1929. During the reign of Adolf Hitler, her father, Heinrich Himmler, commanded the feared Schutzstaffel, known more commonly as the SS. Under his command, the SS played a central part in administering the Holocaust, and carried out a systematic campaign of extermination of millions of civilians in Nazi-occupied Europe. But the Nazi regime collapsed under the weight of the Allied military advance, and on May 20, 1945, Himmler was captured alive by Soviet troops. Shortly thereafter he was transferred to a British-administered prison, where, just days later, he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule that he had with him. Gudrun, who by that time was nearly 16 years old, managed to escape to Italy with her mother, where she was captured by American forces. She testified in the Nuremberg Trials and was eventually released in 1948. She settled with her mother in northern West Germany and lived away from the limelight of publicity until her death on May 24 of this year, aged 88. The unmarked grave of a Dutch-born Nazi spy, who killed himself after spending several months working undercover in wartime Britain, will be marked with a headstone, 76 years after his death by suicide. Born in 1914 in The Hague, Holland, Englebertus Fukken joined the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, the Dutch affiliate of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party led by Adolf Hitler, in 1933. In 1940, shortly after the German invasion of Holland, Fukken, who had been trained as a journalist, was recruited by the Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence. Abwehr’s leadership decided to include Fukken in the ranks of undercover agents sent to Britain in preparation for Operation SEA LION, Germany’s plan to invade Britain.

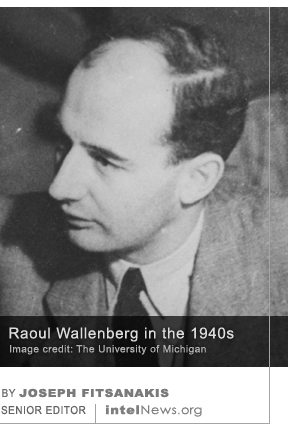

The unmarked grave of a Dutch-born Nazi spy, who killed himself after spending several months working undercover in wartime Britain, will be marked with a headstone, 76 years after his death by suicide. Born in 1914 in The Hague, Holland, Englebertus Fukken joined the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, the Dutch affiliate of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party led by Adolf Hitler, in 1933. In 1940, shortly after the German invasion of Holland, Fukken, who had been trained as a journalist, was recruited by the Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence. Abwehr’s leadership decided to include Fukken in the ranks of undercover agents sent to Britain in preparation for Operation SEA LION, Germany’s plan to invade Britain. The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto.

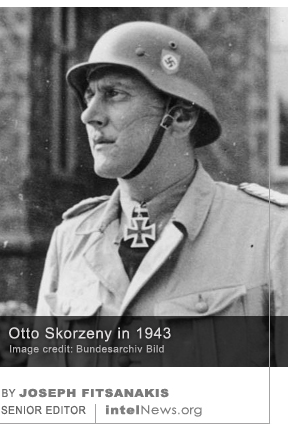

The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto. A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government.

A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government. A congratulatory letter sent by a senior Nazi official to

A congratulatory letter sent by a senior Nazi official to

Research sheds light on Japan’s wartime espionage network inside the United States

September 26, 2022 by Joseph Fitsanakis 1 Comment

The researchers, Ron Drabkin, visiting scholar at the University of Notre Dame, K. Kusunoki, of the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force, and Bradley W. Hart, associate professor at California State University, Fresno, published their work on September 22 in the peer-reviewed journal Intelligence and National Security. Their well-written article is entitled “Agents, Attachés, and Intelligence Failures: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Efforts to Establish Espionage Networks in the United States Before Pearl Harbor”.

Attachés, and Intelligence Failures: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Efforts to Establish Espionage Networks in the United States Before Pearl Harbor”.

The authors acknowledge that the history of the intelligence efforts of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) has received very little attention by scholars. Consequently, it remains unexplored even in Japan, let alone in the international scholarship on intelligence. There are two main reasons for that. To begin with, the IJN systematically destroyed its intelligence files in the months leading to Japan’s official surrender in 1945. Then, following the war, fearing being implicated in war crimes trials, few of its undercover operatives voluntarily revealed their prior involvement in intelligence work.

Luckily, however, the past decade has seen the declassification of a number of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counterintelligence files relating to Japanese intelligence operations targeting the United States. Most of these files date from the 1930s and early 1940s. Additionally, a number of related documents have been declassified by the government of Mexico, which is important, given that Mexico was a major base for Japanese intelligence operations targeting the United States. Read more of this post

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with academic research, espionage, history, HUMINT, Imperial Japanese Navy, Japan, World War II