Declassified files shed light on 1956 disappearance of MI6 agent

October 28, 2015 Leave a comment

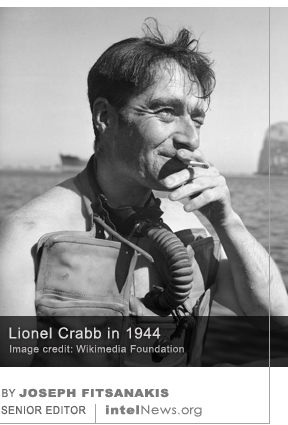

A set of newly released files from the archives of the British Cabinet Office shed light on the mysterious case of a highly decorated combat swimmer, who vanished while carrying out a secret operation against a Soviet ship. The disappearance happened during a historic Soviet high-level visit to Britain in 1956. In April of that year, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, and Nikolai Bulganin, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, arrived in Britain aboard Russian warship Ordzhonikidze, which docked at Portsmouth harbor. Their eight-day tour of Britain marked the first-ever official visit by Soviet leadership to a Western country. But the tour was marred by a botched undersea operation led by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, known commonly as MI6. The operation, which aimed to explore the then state-of-the-art Ordzhonikidze, ended in the disappearance of MI6 diver Lionel “Buster” Crabb. The body of Crabb, one of several MI6 operatives involved in the operation, was never recovered.

A set of newly released files from the archives of the British Cabinet Office shed light on the mysterious case of a highly decorated combat swimmer, who vanished while carrying out a secret operation against a Soviet ship. The disappearance happened during a historic Soviet high-level visit to Britain in 1956. In April of that year, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, and Nikolai Bulganin, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, arrived in Britain aboard Russian warship Ordzhonikidze, which docked at Portsmouth harbor. Their eight-day tour of Britain marked the first-ever official visit by Soviet leadership to a Western country. But the tour was marred by a botched undersea operation led by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, known commonly as MI6. The operation, which aimed to explore the then state-of-the-art Ordzhonikidze, ended in the disappearance of MI6 diver Lionel “Buster” Crabb. The body of Crabb, one of several MI6 operatives involved in the operation, was never recovered.

Now a set of documents released by the Cabinet Office, a British government department tasked with providing support services to the country’s prime minister and senior Cabinet officials, show that the operation had been mismanaged by MI6 from the start. According to The Daily Telegraph, the documents show that miscommunication between the British Foreign Office and MI6 caused the latter to believe that the operation to target the Ordzhonikidze had been authorized by the government, when in fact no such thing had ever occurred.

Moreover, MI6 had housed Crabb and other operatives in a Portsmouth hotel, where the agency’s handler had provided the front-desk clerk with the real names and addresses of the underwater team members. The documents also reveal that several of Crabb’s relatives and friends had been told by him that he would be diving in Portsmouth on the week leading up to his death. Those who knew included one of Crabb’s business partners, with whom he operated a furniture outlet. The partner apparently told the authorities that he was contemplating “consulting a clairvoyant, Madame Theodosia”, in an effort to discover the fate of his missing business partner.

After Crabb disappeared, British government officials were convinced that he had been abducted or killed by the Soviets and that the KGB was in possession of his body. Should the Soviets decide to disclose the existence of the MI6 operation to the world, there would be “no action that [MI6] could take [that] could stave off disaster”, said one British government memo. As intelNews has reported before, n 2007, Eduard Koltsov, a retired Russian military diver, said he killed a man he thinks was Crabb, as he was “trying to place a mine” on the Soviet ship.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 28 October 2015 | Permalink

The president of Chile in the 1970s considered killing his own spy chief in order to conceal his government’s involvement in a terrorist attack in Washington DC, which killed two people, according to declassified memos from the United States Central Intelligence Agency. The target of the attack was Orlando Letelier, a Chilean economist who in the early 1970s served as a senior cabinet minister in the leftwing government of Salvador Allende. But he sought refuge in the US after Allende’s government was deposed in a bloody coup on September 11, 1973, in which Allende was murdered. He taught in several American universities and became a researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) in Washington. At the same time, he publicly pressured the US to break off diplomatic and military ties with the Chilean dictatorship.

The president of Chile in the 1970s considered killing his own spy chief in order to conceal his government’s involvement in a terrorist attack in Washington DC, which killed two people, according to declassified memos from the United States Central Intelligence Agency. The target of the attack was Orlando Letelier, a Chilean economist who in the early 1970s served as a senior cabinet minister in the leftwing government of Salvador Allende. But he sought refuge in the US after Allende’s government was deposed in a bloody coup on September 11, 1973, in which Allende was murdered. He taught in several American universities and became a researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) in Washington. At the same time, he publicly pressured the US to break off diplomatic and military ties with the Chilean dictatorship. Fifty years after the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, Pakistani former soldiers have spoken for the first time about their role in a secret effort by Pakistan to infiltrate India and incite a Muslim uprising. The conflict between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir is largely rooted in Britain’s decision to partition its former colonial possession into mainly Hindu India and Pakistan, a mostly Muslim state. As soon as the British withdrew in 1947, the two states fought a bloody war that culminated in a violent exchange of populations and led to the partition of Kashmir. Today India controls much of the region, which, unlike the rest of the country, is overwhelmingly Muslim. Indian rule survived an uprising by some of the local population in August 1965, which led to yet another war between the two countries, known as the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War.

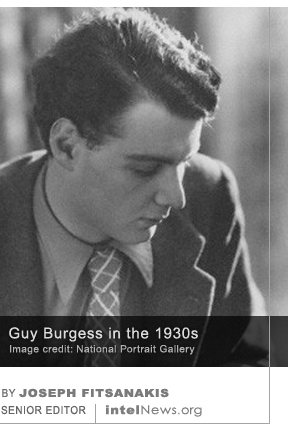

Fifty years after the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, Pakistani former soldiers have spoken for the first time about their role in a secret effort by Pakistan to infiltrate India and incite a Muslim uprising. The conflict between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir is largely rooted in Britain’s decision to partition its former colonial possession into mainly Hindu India and Pakistan, a mostly Muslim state. As soon as the British withdrew in 1947, the two states fought a bloody war that culminated in a violent exchange of populations and led to the partition of Kashmir. Today India controls much of the region, which, unlike the rest of the country, is overwhelmingly Muslim. Indian rule survived an uprising by some of the local population in August 1965, which led to yet another war between the two countries, known as the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War. The life of Guy Burgess, one of the so-called ‘Cambridge Five’ double agents, who spied on Britain for the Soviet Union before defecting to Moscow in 1951, is

The life of Guy Burgess, one of the so-called ‘Cambridge Five’ double agents, who spied on Britain for the Soviet Union before defecting to Moscow in 1951, is  Israeli nuclear whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu, who spent 18 years in prison for revealing the existence of Israel’s nuclear program, has spoken for the first time about his 1986abduction by the Mossad in Rome. Vanunu was an employee at Israel’s top-secret Negev Nuclear Research Center, located in the desert city of Dimona, which was used to develop the country’s nuclear arsenal. But he became a fervent opponent of nuclear proliferation and in 1986 fled to the United Kingdom, where he revealed the existence of the Israeli nuclear weapons program to the The Times of London. His action was in direct violation of the non-disclosure agreement he had signed with the government of Israel; moreover, it went against Israel’s official policy of ‘nuclear ambiguity’, which means that the country refuses to confirm or deny that it maintains a nuclear weapons program.

Israeli nuclear whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu, who spent 18 years in prison for revealing the existence of Israel’s nuclear program, has spoken for the first time about his 1986abduction by the Mossad in Rome. Vanunu was an employee at Israel’s top-secret Negev Nuclear Research Center, located in the desert city of Dimona, which was used to develop the country’s nuclear arsenal. But he became a fervent opponent of nuclear proliferation and in 1986 fled to the United Kingdom, where he revealed the existence of the Israeli nuclear weapons program to the The Times of London. His action was in direct violation of the non-disclosure agreement he had signed with the government of Israel; moreover, it went against Israel’s official policy of ‘nuclear ambiguity’, which means that the country refuses to confirm or deny that it maintains a nuclear weapons program. Frederick Forsyth, the esteemed British author of novels such as The Day of the Jackal, has confirmed publicly for the first time that he was an agent of British intelligence for two decades. Forsyth, who is 77, worked for many decades as an international correspondent for the BBC and Reuters news agency, covering some of the world’s most sensitive areas, including postcolonial Nigeria, apartheid South Africa and East Germany during the Cold War. But he became famous for authoring novels that have sold over 70 million copies worldwide, including The Odessa File, Dogs of War and The Day of the Jackal, many of which were adapted into film. Several of his intelligence-related novels are based on his experiences as a news correspondent, which have prompted his loyal fans to suspect that he might have some intelligence background.

Frederick Forsyth, the esteemed British author of novels such as The Day of the Jackal, has confirmed publicly for the first time that he was an agent of British intelligence for two decades. Forsyth, who is 77, worked for many decades as an international correspondent for the BBC and Reuters news agency, covering some of the world’s most sensitive areas, including postcolonial Nigeria, apartheid South Africa and East Germany during the Cold War. But he became famous for authoring novels that have sold over 70 million copies worldwide, including The Odessa File, Dogs of War and The Day of the Jackal, many of which were adapted into film. Several of his intelligence-related novels are based on his experiences as a news correspondent, which have prompted his loyal fans to suspect that he might have some intelligence background. The British government has released a nine-volume file on an influential film critic who

The British government has released a nine-volume file on an influential film critic who  A Soviet double spy was able to penetrate the senior echelons of Australia’s intelligence agency during the Cold War, according to a retired Australian intelligence officer who has spoken out for the first time. Molly Sasson, was born in Britain, but worked for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) from 1969 until her retirement in 1983. A fluent German speaker, Sasson was first recruited during World War II by the Royal Air Force, where she worked as an intelligence officer before transferring to the Security Service (MI5), Britain’s domestic intelligence agency. At the onset of the Cold War, Sasson helped facilitate the defection to Britain of Colonel Grigori Tokaty, an influential rocket scientist who later became a professor of aeronautics in London. But in the late 1960s, Sasson moved with her husband to Australia, where she took up a job with ASIO, following a personal invitation by its Director, Sir Charles Spry. Upon her arrival in Canberra, Sasson took a post with ASIO’s Soviet counterintelligence desk, which monitored Soviet espionage activity on Australian soil.

A Soviet double spy was able to penetrate the senior echelons of Australia’s intelligence agency during the Cold War, according to a retired Australian intelligence officer who has spoken out for the first time. Molly Sasson, was born in Britain, but worked for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) from 1969 until her retirement in 1983. A fluent German speaker, Sasson was first recruited during World War II by the Royal Air Force, where she worked as an intelligence officer before transferring to the Security Service (MI5), Britain’s domestic intelligence agency. At the onset of the Cold War, Sasson helped facilitate the defection to Britain of Colonel Grigori Tokaty, an influential rocket scientist who later became a professor of aeronautics in London. But in the late 1960s, Sasson moved with her husband to Australia, where she took up a job with ASIO, following a personal invitation by its Director, Sir Charles Spry. Upon her arrival in Canberra, Sasson took a post with ASIO’s Soviet counterintelligence desk, which monitored Soviet espionage activity on Australian soil. In 2007 I wrote in my “

In 2007 I wrote in my “ The final piece of sealed testimony in one of the most important espionage cases of the Cold War has been released, 64 years after it was given. The case led to the execution in 1953 of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, an American couple who were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. The Rosenbergs were arrested in 1950 for being members of a larger Soviet-handled spy ring, which included Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass. Greenglass agreed to testify for the US government in order to save his life, as well as the life of his wife, Ruth, who was also involved in the spy ring. He subsequently fingered Julius Rosenberg as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets, and Ethel as the person who retyped the content of classified documents before they were surrendered to their handlers. That piece of testimony from Greenglass the primary evidence used to convict and execute the Rosenbergs.

The final piece of sealed testimony in one of the most important espionage cases of the Cold War has been released, 64 years after it was given. The case led to the execution in 1953 of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, an American couple who were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. The Rosenbergs were arrested in 1950 for being members of a larger Soviet-handled spy ring, which included Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass. Greenglass agreed to testify for the US government in order to save his life, as well as the life of his wife, Ruth, who was also involved in the spy ring. He subsequently fingered Julius Rosenberg as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets, and Ethel as the person who retyped the content of classified documents before they were surrendered to their handlers. That piece of testimony from Greenglass the primary evidence used to convict and execute the Rosenbergs. A Soviet double spy, who secretly defected to Britain 30 years ago this month, has revealed for the first time the details of his exfiltration by British intelligence in 1985. Oleg Gordievsky was one of the highest Soviet intelligence defectors to the West in the closing stages of the Cold War. He joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, eventually reaching the rank of colonel. But in the 1960s, while serving in the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen, Denmark, Gordievsky began feeling disillusioned about the Soviet system. His doubts were reinforced by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was soon afterwards that he made the decision to contact British intelligence.

A Soviet double spy, who secretly defected to Britain 30 years ago this month, has revealed for the first time the details of his exfiltration by British intelligence in 1985. Oleg Gordievsky was one of the highest Soviet intelligence defectors to the West in the closing stages of the Cold War. He joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, eventually reaching the rank of colonel. But in the 1960s, while serving in the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen, Denmark, Gordievsky began feeling disillusioned about the Soviet system. His doubts were reinforced by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was soon afterwards that he made the decision to contact British intelligence. A set of declassified intelligence documents from the 1950s and 1960s offer a glimpse into the secret war fought in Canada between American and Soviet spy agencies at the height of the Cold War. The documents were authored by the United States Central Intelligence Agency and declassified following a Freedom of Information Act request filed on behalf of the Canadian newspaper The Toronto Star.

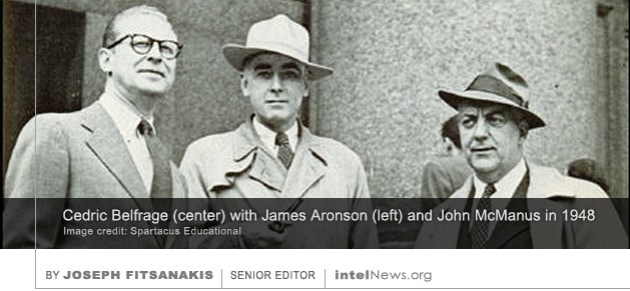

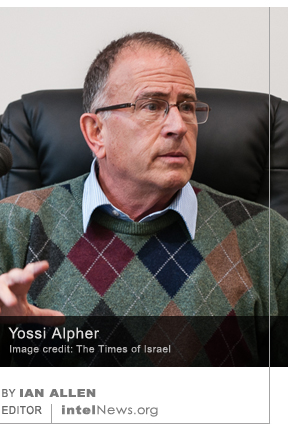

A set of declassified intelligence documents from the 1950s and 1960s offer a glimpse into the secret war fought in Canada between American and Soviet spy agencies at the height of the Cold War. The documents were authored by the United States Central Intelligence Agency and declassified following a Freedom of Information Act request filed on behalf of the Canadian newspaper The Toronto Star.  Yossi Alpher, a former Israeli intelligence officer, who was directly involved in numerous top-secret operations during his spy career, has published a new book that analyzes the overarching strategy behind Israel’s spy operations. Alpher served in Israeli Military Intelligence before joining the Mossad, where he served until 1980. Upon retiring from the Mossad, he joined Tel Aviv University’s Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, which he eventually directed. Throughout his career in intelligence, Alpher worked or liaised with every Israeli spy agency, including the Shin Bet –the country’s internal security service.

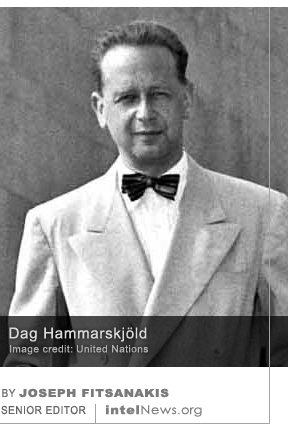

Yossi Alpher, a former Israeli intelligence officer, who was directly involved in numerous top-secret operations during his spy career, has published a new book that analyzes the overarching strategy behind Israel’s spy operations. Alpher served in Israeli Military Intelligence before joining the Mossad, where he served until 1980. Upon retiring from the Mossad, he joined Tel Aviv University’s Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, which he eventually directed. Throughout his career in intelligence, Alpher worked or liaised with every Israeli spy agency, including the Shin Bet –the country’s internal security service. A panel of experts commissioned by the United Nations is about to unveil fresh evidence on the mysterious death in 1961 of UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld, who some claim was murdered for supporting African decolonization. The evidence could spark a new official probe into the incident, which has been called “one of the enduring mysteries of the 20th century”.

A panel of experts commissioned by the United Nations is about to unveil fresh evidence on the mysterious death in 1961 of UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld, who some claim was murdered for supporting African decolonization. The evidence could spark a new official probe into the incident, which has been called “one of the enduring mysteries of the 20th century”.

Chile government report says poet Neruda may have been poisoned

November 9, 2015 by Joseph Fitsanakis Leave a comment

The death of the internationally acclaimed poet, who was 69 at the time, was officially attributed to prostate cancer and the effects of acute mental stress caused by the military coup. In 2013, however, an official investigation was launched into Neruda’s death following allegations that he had been murdered. The investigation was sparked by comments made by Neruda’s personal driver, Manuel Araya, who said that the poet had been deliberately injected with poison while receiving treatment for cancer at the Clinica Santa Maria in Chilean capital Santiago. According to Araya, General Pinochet ordered Neruda’s assassination after he was told that the poet was preparing to seek political asylum in Mexico. The Chilean dictatorship allegedly feared that the Nobel laureate poet would seek to form a government-in-exile and oppose the regime of General Pinochet.

In April of that year, a complex autopsy was performed on Neruda’s exhumed remains, but was inconclusive. On November 6, however, Spanish newspaper El País said it had been given access to a report prepared by Chile’s Ministry of the Interior. The report allegedly argues that it was unlikely that Neruda’s death was the “consequence of his prostate cancer”. According to El País, the document states that it was “manifestly possible and highly probable” that the poet’s death was the outcome of “direct intervention by third parties”. The report also explains that Neruda’s alleged murder resulted from a fast-acting substance that was injected into his body or entered it orally.

The report obtained by El País was produced for an ongoing legal probe into Neruda’s death, which is being supervised by Mario Carroza Espinosa, one of Chile’s most high-profile judges.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 09 October 2015 | Permalink | News tip: R.W.

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Chile, Cold War, history, News, Pablo Neruda, poisoning, Salvador Allende, suspicious deaths