November 1, 2017

by Joseph Fitsanakis

News reports hastened to describe Tuesday’s atrocity in Lower Manhattan as “the worst terror attack in New York since September 11, 2001”. The comparison may be numerically accurate. Moreover, the deaths caused by the attack are nothing short of tragic. But if the Islamic State’s deadliest response to its retreat in the Middle East is a clumsy truck driver armed with a pellet gun, then Americans have little to fear from the terrorist group.

News reports hastened to describe Tuesday’s atrocity in Lower Manhattan as “the worst terror attack in New York since September 11, 2001”. The comparison may be numerically accurate. Moreover, the deaths caused by the attack are nothing short of tragic. But if the Islamic State’s deadliest response to its retreat in the Middle East is a clumsy truck driver armed with a pellet gun, then Americans have little to fear from the terrorist group.

For months now, Western counter-terrorism experts have been bracing for a change of tactics by the Sunni group, which in 2014 controlled territory in Iraq and Syria equal to the size of England. The prevailing theory in security circles is that, as the Islamic State is forced to retreat in the Middle East, it will unleash waves of sleeper cells against Western targets abroad. This concern is logical, given the militant group’s obsession with its public image. At every turn since its dramatic rise in 2013, the Islamic State has consciously tried to project an appearance of strength that is far greater than its actual capabilities. In its public statements, the group has consistently extolled its ability to strike at distant targets regardless of its territorial strength in the Middle East. This applies especially to attacks by the Islamic State in Europe, which have tended to come in response to intense media speculation that the group’s territorial hold may be weakening.

One presumes that a terrorist attack in New York, a symbolic site in the ‘war on terrorism’, would aim to do just that: namely project an image of continuing strength and convince global audiences that the group remains potent. Yet, despite the tragic loss of eight lives, Tuesday’s attack in Manhattan did nothing of the sort.

To begin with, an attack on cyclists with a rented utility vehicle is hardly ground-breaking at this point. In the past 18 months, we have seen similar types of attacks in London (on two separate occasions), in Barcelona’s Las Ramblas mall, in downtown Berlin, and in Nice, where a 19-ton cargo truck was used to kill 86 people. Terrorist groups are by nature conservative in their operations, preferring to use low-tech, time-tested methods to dispense  violence, rather than risk failure by breaking new ground. But at a time like this, when the very existence of the Islamic State hangs in the balance, one would think that the group would consciously try to intimidate its opponents by showing off some kind of revolutionary new weapon. That did not happen on Tuesday.

violence, rather than risk failure by breaking new ground. But at a time like this, when the very existence of the Islamic State hangs in the balance, one would think that the group would consciously try to intimidate its opponents by showing off some kind of revolutionary new weapon. That did not happen on Tuesday.

Additionally, the perpetrator of the attack, Uzbek immigrant Sayfullo Saipov, is hardly an inspiring figure for Islamic State supporters. After running over a group of unsuspecting cyclists, the 29-year-old Florida resident clumsily smashed his rented truck head-on into a vehicle that was far larger and heavier than his own, thus completely destroying his vehicle’s engine and effectively disabling his only weapon. He then jumped out of the truck, apparently wielding a pellet gun and a paintball gun. Mobile phone footage captured from a nearby building shows Saipov walking in a disoriented manner through Manhattan traffic before being shot by police officers. If —as it seems— the Islamic State was behind that attack, it would mean that modern history’s most formidable terrorist group failed to get a pistol in a country where firearms are in some cases easier to secure than nasal decongestant.

Choice of weapon aside, one does not need to be a counter-terrorism expert to conclude that Saipov lacked basic operational and planning skills. His attack behavior shows that he had failed to carry out even rudimentary prior reconnaissance of the area where he launched his attack. He even appears to have failed to read Tuesday’s New York Post. Had he done so, he would have known that  the heavily attended annual Village Halloween Parade was scheduled to take place on the very same street, just two hours after he launched his deranged attack.

the heavily attended annual Village Halloween Parade was scheduled to take place on the very same street, just two hours after he launched his deranged attack.

Once again, the question is: if the Islamic State does not utilize its deadliest and most capable operatives now, when its very existence in its Middle Eastern stronghold is being directly challenged, then when will it do so? By all accounts, the militant group’s leaders are well-read on recent history. They are therefore fully aware that, in the post-9/11 age, clumsy, low-tech, limited terrorist strikes by lone-wolf operatives lack the capacity to intimidate civilian populations, especially in New York.

Western counter-terrorism agencies and citizens alike should remain vigilant; but early evidence shows that the Islamic State is simply too weak to launch sophisticated, large-scale strikes against Western targets abroad. As I have argued before, the threat level would change if the militant group acquires chemical weapons or other tools of mass terrorism. For now, however, it is safe to state that the Islamic State’s capabilities do not pose anything close to an existential threat to the West.

► About the author: Dr. Joseph Fitsanakis is Associate Professor in the Intelligence and National Security Studies program at Coastal Carolina University. Before joining Coastal, Dr. Fitsanakis built the Security and Intelligence Studies program at King University, where he also directed the King Institute for Security and Intelligence Studies. He is also deputy director of the European Intelligence Academy and senior editor at intelNews.org.

Relations between Russia and much of the West reached a new low on Monday, with the expulsion of over 100 Russian diplomats from two dozen countries around the world. The unprecedented expulsions were publicized on Monday with a series of coordinated announcements issued from nearly every European capital, as well as from Washington, Ottawa and Canberra. By the early hours of Tuesday, the number of Russian diplomatic expulsions had reached 118 —not counting the 23 Russian so-called “undeclared intelligence officers” that were expelled from Britain last week. Further expulsions of Russian diplomats are expected in the coming days.

Relations between Russia and much of the West reached a new low on Monday, with the expulsion of over 100 Russian diplomats from two dozen countries around the world. The unprecedented expulsions were publicized on Monday with a series of coordinated announcements issued from nearly every European capital, as well as from Washington, Ottawa and Canberra. By the early hours of Tuesday, the number of Russian diplomatic expulsions had reached 118 —not counting the 23 Russian so-called “undeclared intelligence officers” that were expelled from Britain last week. Further expulsions of Russian diplomats are expected in the coming days. predecessor, Barack Obama, and his Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who is known for her hardline anti-Russian stance. In Europe, the move to expel dozens of Russian envoys from 23 different countries —most of them European Union members— was a rare act of unity that surprised European observers as much as it did the Russians.

predecessor, Barack Obama, and his Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who is known for her hardline anti-Russian stance. In Europe, the move to expel dozens of Russian envoys from 23 different countries —most of them European Union members— was a rare act of unity that surprised European observers as much as it did the Russians. As expected, Moscow snubbed the British government’s demand for information into how a Russian-produced military-grade nerve agent ended up being used in the streets of Salisbury, England. As British Prime Minister Theresa May addressed the House of Commons on Wednesday afternoon, Sergei Skripal continued to fight for his life in a hospital in southern England. His daughter, Yulia, was also comatose, having been poisoned with the same Cold-War-era nerve agent as her father. This blog has

As expected, Moscow snubbed the British government’s demand for information into how a Russian-produced military-grade nerve agent ended up being used in the streets of Salisbury, England. As British Prime Minister Theresa May addressed the House of Commons on Wednesday afternoon, Sergei Skripal continued to fight for his life in a hospital in southern England. His daughter, Yulia, was also comatose, having been poisoned with the same Cold-War-era nerve agent as her father. This blog has  the latest expulsions are dwarfed by the dramatic expulsion in 1971 of no fewer than 105 Soviet diplomats from Britain, following yet another defection of a Soviet intelligence officer, who remained anonymous.

the latest expulsions are dwarfed by the dramatic expulsion in 1971 of no fewer than 105 Soviet diplomats from Britain, following yet another defection of a Soviet intelligence officer, who remained anonymous. Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The

Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The  Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky.

Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky. from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success.

from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success. Latvian defense officials have hinted that Russia is trying to destabilize Latvia’s economy, as a Western-backed anti-corruption probe at the highest levels of the Baltic country’s banking sector deepens. Developments have progressed at a high speed since Monday of last week, when Latvia’s Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau

Latvian defense officials have hinted that Russia is trying to destabilize Latvia’s economy, as a Western-backed anti-corruption probe at the highest levels of the Baltic country’s banking sector deepens. Developments have progressed at a high speed since Monday of last week, when Latvia’s Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau  The British government has announced that it will form a new intelligence unit tasked with preventing the spread of so-called “fake news” by foreign states, including Russia. The decision was revealed earlier this week in London by a government spokesman, who said that the new unit will be named “National Security Communications Unit”. The spokesman added that the unit will be responsible for “combating disinformation by state actors and others”. When asked by reporters whether the effort was meant as a response to the phenomenon often described as “fake news”, the spokesman said that it was.

The British government has announced that it will form a new intelligence unit tasked with preventing the spread of so-called “fake news” by foreign states, including Russia. The decision was revealed earlier this week in London by a government spokesman, who said that the new unit will be named “National Security Communications Unit”. The spokesman added that the unit will be responsible for “combating disinformation by state actors and others”. When asked by reporters whether the effort was meant as a response to the phenomenon often described as “fake news”, the spokesman said that it was. An investigative journalist in Finland, who recently co-authored an exposé of a Finnish intelligence program targeting Russia, destroyed her computer with a hammer, prompting police to enter her house on Sunday. The journalist, Laura Halminen, co-wrote the exposé with her colleague, Tuomo Pietiläinen. Titled “The Secret Behind the Cliff”, the article

An investigative journalist in Finland, who recently co-authored an exposé of a Finnish intelligence program targeting Russia, destroyed her computer with a hammer, prompting police to enter her house on Sunday. The journalist, Laura Halminen, co-wrote the exposé with her colleague, Tuomo Pietiläinen. Titled “The Secret Behind the Cliff”, the article  Authorities in Poland have charged three high-level military intelligence officials with acting in the interests of Russia. The three include two former directors of Polish military intelligence and are facing sentences of up to 10 years in prison. The news broke on December 6, when Polish authorities announced the arrest of Piotr Pytel, who was director of Poland’s Military Counterintelligence Service (SKW) from 2014 to 2015. It soon emerged that two more arrests had taken place, that of Pytel’s predecessor, Janusz Nosek, and Krzysztof Dusza, Pytel’s chief of staff during his tenure as SKW director.

Authorities in Poland have charged three high-level military intelligence officials with acting in the interests of Russia. The three include two former directors of Polish military intelligence and are facing sentences of up to 10 years in prison. The news broke on December 6, when Polish authorities announced the arrest of Piotr Pytel, who was director of Poland’s Military Counterintelligence Service (SKW) from 2014 to 2015. It soon emerged that two more arrests had taken place, that of Pytel’s predecessor, Janusz Nosek, and Krzysztof Dusza, Pytel’s chief of staff during his tenure as SKW director. Files released on Monday by the British government reveal new evidence about one of the most prolific Soviet spy rings that operated in the West after World War II, which became known as the Portland Spy Ring. Some of the members of the Portland Spy Ring were Soviet operatives who, at the time of their arrest, posed as citizens of third countries. All were non-official-cover intelligence officers, or NOCs, as they are known in Western intelligence parlance. Their Soviet —and nowadays Russian— equivalents are known as illegals. NOCs are high-level principal agents or officers of an intelligence agency, who operate without official connection to the authorities of the country that employs them. During much of the Cold War, NOCs posed as business executives, students, academics, journalists, or non-profit agency workers. Unlike official-cover officers, who are protected by diplomatic immunity, NOCs have no such protection. If arrested by authorities of their host country, they can be tried and convicted for engaging in espionage.

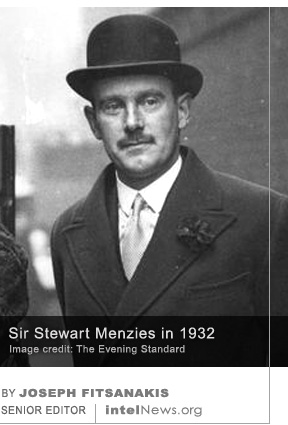

Files released on Monday by the British government reveal new evidence about one of the most prolific Soviet spy rings that operated in the West after World War II, which became known as the Portland Spy Ring. Some of the members of the Portland Spy Ring were Soviet operatives who, at the time of their arrest, posed as citizens of third countries. All were non-official-cover intelligence officers, or NOCs, as they are known in Western intelligence parlance. Their Soviet —and nowadays Russian— equivalents are known as illegals. NOCs are high-level principal agents or officers of an intelligence agency, who operate without official connection to the authorities of the country that employs them. During much of the Cold War, NOCs posed as business executives, students, academics, journalists, or non-profit agency workers. Unlike official-cover officers, who are protected by diplomatic immunity, NOCs have no such protection. If arrested by authorities of their host country, they can be tried and convicted for engaging in espionage. Successive directors of the Secret Intelligence Service used a secret slush fund to finance spy operations without British government oversight after World War II, according to a top-secret document unearthed in London. The document was found in a collection belonging to the personal archive of the secretary of the British cabinet, which was released by the United Kingdom’s National Archives. It was discovered earlier this year by Dr Rory Cormac, Associate Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Nottingham in England. It forms the basis of an episode of BBC Radio 4’s investigative history program, Document, which

Successive directors of the Secret Intelligence Service used a secret slush fund to finance spy operations without British government oversight after World War II, according to a top-secret document unearthed in London. The document was found in a collection belonging to the personal archive of the secretary of the British cabinet, which was released by the United Kingdom’s National Archives. It was discovered earlier this year by Dr Rory Cormac, Associate Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Nottingham in England. It forms the basis of an episode of BBC Radio 4’s investigative history program, Document, which  Political affairs in Zimbabwe took an unprecedented turn on Monday, as the chief of the armed forces warned the country’s President, Robert Mugabe, that the military would “not hesitate to step in” to stop infighting within the ruling party. General Constantino Chiwenga, Commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, took the extremely rare step of summoning reporters for a press conference at the military’s headquarters in Harare on Monday. A direct intervention of this kind is unprecedented in the politics of Zimbabwe, a country that is tightly ruled by its authoritarian President, Robert Mugabe. Mugabe is also President and First Secretary of the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), the party that has dominated Zimbabwean politics since it assumed power in 1980.

Political affairs in Zimbabwe took an unprecedented turn on Monday, as the chief of the armed forces warned the country’s President, Robert Mugabe, that the military would “not hesitate to step in” to stop infighting within the ruling party. General Constantino Chiwenga, Commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, took the extremely rare step of summoning reporters for a press conference at the military’s headquarters in Harare on Monday. A direct intervention of this kind is unprecedented in the politics of Zimbabwe, a country that is tightly ruled by its authoritarian President, Robert Mugabe. Mugabe is also President and First Secretary of the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), the party that has dominated Zimbabwean politics since it assumed power in 1980. Dozens of Saudi senior figures, some of them among the world’s wealthiest people, have been fired or arrested, as the king and his son appeared to be removing their last remaining critics from the ranks of the security services. The unprecedented arrests took place without warning less than two hours after state-run media announced the creation of a new “supreme committee to combat corruption”. A

Dozens of Saudi senior figures, some of them among the world’s wealthiest people, have been fired or arrested, as the king and his son appeared to be removing their last remaining critics from the ranks of the security services. The unprecedented arrests took place without warning less than two hours after state-run media announced the creation of a new “supreme committee to combat corruption”. A  News reports hastened to

News reports hastened to  violence, rather than risk failure by breaking new ground. But at a time like this, when the very existence of the Islamic State hangs in the balance, one would think that the group would consciously try to intimidate its opponents by showing off some kind of revolutionary new weapon. That did not happen on Tuesday.

violence, rather than risk failure by breaking new ground. But at a time like this, when the very existence of the Islamic State hangs in the balance, one would think that the group would consciously try to intimidate its opponents by showing off some kind of revolutionary new weapon. That did not happen on Tuesday. the heavily attended annual Village Halloween Parade was scheduled to take place on the very same street, just two hours after he launched his deranged attack.

the heavily attended annual Village Halloween Parade was scheduled to take place on the very same street, just two hours after he launched his deranged attack. In a surprise move, the president of Mozambique has fired the head of the military and the director of the country’s intelligence service, two weeks after attacks by an unidentified group left 16 people dead in a northern town. The attacks occurred on October 5 and 6 in Mocimboa da Praia, a small town of about 30,000 people located along Mozambique’s extreme northern coastline. The town lies only a few miles south of Mozambique’s border with Tanzania and within sight of several offshore gas fields in the Indian Ocean. According to local

In a surprise move, the president of Mozambique has fired the head of the military and the director of the country’s intelligence service, two weeks after attacks by an unidentified group left 16 people dead in a northern town. The attacks occurred on October 5 and 6 in Mocimboa da Praia, a small town of about 30,000 people located along Mozambique’s extreme northern coastline. The town lies only a few miles south of Mozambique’s border with Tanzania and within sight of several offshore gas fields in the Indian Ocean. According to local  A German newspaper reported last week that at least one European intelligence agency has already warned that the Islamic State is exploring the use of chemicals for attacks in Europe. Such an eventuality would be a radical departure from prior attacks by the Islamic State in the West. In the past, the militant group has shown a strong preference for low-tech means of dispensing violence, such as firearms, vehicles and knives. But it has utilized chemical substances in Iraq and Syria, and its technical experts have amassed significant knowledge about weaponized chemicals.

A German newspaper reported last week that at least one European intelligence agency has already warned that the Islamic State is exploring the use of chemicals for attacks in Europe. Such an eventuality would be a radical departure from prior attacks by the Islamic State in the West. In the past, the militant group has shown a strong preference for low-tech means of dispensing violence, such as firearms, vehicles and knives. But it has utilized chemical substances in Iraq and Syria, and its technical experts have amassed significant knowledge about weaponized chemicals.

Opinion: Bizarre fake murder plot points to Ukrainian state’s recklessness, unreliability

June 1, 2018 by Joseph Fitsanakis 4 Comments

Arkady Babchenko

Western audiences were treated to a small taste of the bizarreness of Eastern European politics this week, when a Russian journalist who had reportedly been assassinated by the Kremlin, made an appearance at a live press conference held in Kiev. On Tuesday, Ukrainian media reported that Arkady Babchenko, a Russian war correspondent based in Ukraine, had been shot dead outside his apartment in the Ukrainian capital. A day later, after Babchenko’s murder had prompted global headlines pointing to Russia as the most likely culprit, Babchenko suddenly

appeared alive and well during a press conference held by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). The SBU then said that Babchenko’s killing had been staged in an attempt to derail a Russian-sponsored plan to kill him. The bizarre incident concluded with Babchenko meeting on live television with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who praised him as a hero. Later that night, the Russian journalist wrote on his Facebook page that he planned to die after “dancing on [Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s grave”.

Welcome to Ukraine, a strange, corrupt and ultra-paranoid state that is on the front lines of what some describe as a new Cold War between the West and Russia. Like the Cold War of the last century, the present confrontation is fought largely through information. The Russian government, which appears to be far more skillful than its Western adversaries in utilizing information for political purposes, immediately sought to capitalize on the Babchenko case. In fact, this baffling and inexplicable fiasco may be said to constitute one of the greatest propaganda victories for the Kremlin in years.

Ever since accusations began to surface in the Western media about Moscow’s alleged involvement in the 2016 presidential elections in the United States, Russia has dismissed these claims as “fake news” and anti-Russian disinformation. When Sergei and Yulia Skripal were poisoned in England in March, the Kremlin called it a false-flag operation. This is a technical term that describes a military or intelligence activity that seeks to conceal the role of the sponsoring party, while at the same time placing blame on another, unsuspecting, party. Most Western observes reject Russia’s dismissals, and see the Kremlin as the most likely culprit behind the attempt to kill the Skripals.

As one would expect, Russia stuck to its guns on Tuesday, when the world’s media announced the death of Arkady Babchenko in the Ukraine. Moscow claimed once again that we were dealing here with a false flag operation that was orchestrated by anti-Kremlin circles to make Russia look bad at home and abroad. It turns out that Moscow was right. Babchenko’s “murder” was indeed a false flag operation —admittedly a sloppy, shoddy and incredibly clumsy false flag operation, but a false flag operation nonetheless. Moreover, Babchenko’s staged killing could not possibly have come at a worse time for Ukraine and its Western allies. In the current environment, global public opinion is extremely sensitive to the phenomenon of ‘fake news’ and disinformation. Within this broader context, the Ukrainian state and its intelligence institutions have placed themselves at the center of an global disinformation maelstrom that will take a long time to subside. In doing so, the government of Ukraine has irreparably harmed its reputation among the general public and in the eyes of its Western allies. The Kremlin could not possibly have asked for a better gift from its Ukrainian adversaries.

The amateurishness and recklessness of some Eastern European countries that the West sees as allies in its confrontation with Russia, such as Ukraine, Poland, Hungary, and others, would be humorous if it were not so dangerous. The manifest idiocy of the Babchenko fake plot also poses serious questions about the West’s policy vis-à-vis Russia. It is one thing for the West to be critical of the Kremlin and its policies —both domestic and foreign. It is quite another for it to place its trust on governments and intelligence services as those of Ukraine, which are clearly unreliable, unprofessional, and appear to lack basic understanding of the role of information in international affairs.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 01 June 2018 | Permalink

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Analysis, Arkady Babchenko, deception operations, false flag operations, Joseph Fitsanakis, Newstex, Russia, SBU (Ukraine), Ukraine