March 8, 2018

by Joseph Fitsanakis

Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal last Sunday in England fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert operation in almost every way.

Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal last Sunday in England fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert operation in almost every way.

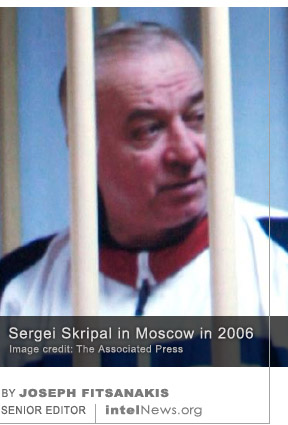

Some have expressed surprise that Skripal, a Russian intelligence officer who was jailed in 2004 for selling Moscow’s secrets to British spies, would have been targeted by the Russian state. Before being allowed to resettle in the British countryside in 2010, Skripal was officially pardoned by the Kremlin. He was then released from prison along with four other Russian double agents, in exchange for 10 Russian deep-cover spies who had been caught in the United States earlier that year. According to this argument, “a swap has been a guarantee of peaceful retirement” in the past. Thus killing a pardoned spy who has been swapped with some of your own violates the tacit rules of espionage, which exist even between bitter rivals like Russia and the United States.

This assumption, however, is baseless. There are no rules in espionage, and swapped spies are no safer than defectors, especially if they are judged to have caused significant damage to their employers. It is also generally assumed that pardoned spies who are allowed to resettle abroad will fade into retirement, not continue to work for their foreign handlers, as was the case with  Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky.

Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky.

On Wednesday, the Metropolitan Police Service announced that Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia, 33, had been “targeted specifically” by a nerve agent. The official announcement stopped short of specifying the nerve agent used, but experts point to sarin gas or VX. Both substances are highly toxic and compatible with the clinical symptoms reportedly displayed by the Skripals when they were found in a catatonic state by an ambulance crew and police officers last Sunday. At least one responder, reportedly a police officer, appears to have also been affected by the nerve agent. All three patients are reported to be in a coma. They are lucky to have survived at all, given that nerve agents inhaled through the respiratory system work by debilitating the body’s respiratory muscles, effectively causing the infected organism to die from suffocation.

In the past 24 hours, at least one British newspaper stated that the two Russians were “poisoned by a very rare nerve agent, which only a few laboratories in the world could have produced”. That is not quite true. It would be more accurate to say that few laboratories in the world would dare to produce sarin or VX, which is classified as a weapon of mass destruction. But no advanced mastering of chemistry or highly specialist laboratories are needed to manufacture these agents. Indeed, those with knowledge of military history will know that they were produced in massive quantities prior to and during World War II. Additionally —unlike polonium, which was used to kill Litvinenko in 2006— nerve gas could be produced in situ and would not need to be imported  from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success.

from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success.

By Wednesday, the British security services were reportedly using “hundreds of detectives, forensic specialists, analysts and intelligence officers working around the clock” to find “a network of highly-trained assassins” who are “either present or past state-sponsored actors”. Such actors were almost certainly behind the targeted attack on the Skripals. They must have dispensed the lethal agent in liquid, aerosol or a gas form, either by coming into direct physical contact with their victims, or by using a timed device. Regardless, the method used would have been designed to give the assailants the necessary time to escape unharmed. Still, there are per capita more CCTV cameras in Britain than in any other country in the world, which gives police investigators hope that they may be able to detect the movements of the attackers. It is highly unlikely that the latter remain on British soil. But if they are, and are identified or caught, it is almost certain that they will be found to have direct links with a foreign government.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 08 March 2018 | Permalink

The nerve agent that poisoned a Russian double spy in England last week may have been smeared on his car’s door handle, according to sources. Sergei Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia, 33, are in critical condition after being poisoned on March 4 by unknown assailants in the English town of Salisbury. Skripal, a Russian former military intelligence officer, has been living there since 2010, when he was released from a Russian prison after serving half of a 13-year sentence for spying for Britain. The British government said on Monday that it believes Skripal and his daughter were poisoned by a military-grade nerve agent, thought to have been built in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Britain’s counterterrorism experts continue to compile evidence on the case. Moscow denies any involvement.

The nerve agent that poisoned a Russian double spy in England last week may have been smeared on his car’s door handle, according to sources. Sergei Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia, 33, are in critical condition after being poisoned on March 4 by unknown assailants in the English town of Salisbury. Skripal, a Russian former military intelligence officer, has been living there since 2010, when he was released from a Russian prison after serving half of a 13-year sentence for spying for Britain. The British government said on Monday that it believes Skripal and his daughter were poisoned by a military-grade nerve agent, thought to have been built in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Britain’s counterterrorism experts continue to compile evidence on the case. Moscow denies any involvement. The British prime minister said on Monday that it was “highly likely” the nerve agent used to attack a Russian defector in England last week was developed by Russia. But sources in London told the BBC that the British government would not invoke Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which states that an attack on one member of the alliance is an attack on all. Theresa May was referring to an

The British prime minister said on Monday that it was “highly likely” the nerve agent used to attack a Russian defector in England last week was developed by Russia. But sources in London told the BBC that the British government would not invoke Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which states that an attack on one member of the alliance is an attack on all. Theresa May was referring to an  The British secret services have begun tightening the physical security of dozens of Russian defectors living in Britain, a week after the attempted murder of former KGB Colonel Sergei Skripal in southern England. The 66-year-old double spy and his daughter, Yulia, were found in a catatonic state in the town of Salisbury on March 4. It was later determined that they had been attacked with a nerve agent. Russian officials have vehemently denied that the Kremlin had any involvement with the brazen attempt to kill Skripal. But,

The British secret services have begun tightening the physical security of dozens of Russian defectors living in Britain, a week after the attempted murder of former KGB Colonel Sergei Skripal in southern England. The 66-year-old double spy and his daughter, Yulia, were found in a catatonic state in the town of Salisbury on March 4. It was later determined that they had been attacked with a nerve agent. Russian officials have vehemently denied that the Kremlin had any involvement with the brazen attempt to kill Skripal. But,  Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The

Most state-sponsored assassinations tend to be covert operations, which means that the sponsoring party cannot be conclusively identified, even if it is suspected. Because of their covert nature, assassinations tend to be extremely complex intelligence-led operations, which are designed to provide plausible deniability to their sponsors. Consequently, the planning and implementation of these operations usually involves a large number of people, each with a narrow set of unique skills. But —and herein lies an interesting contradiction— their execution is invariably simple, both in style and method. The  Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky.

Skripal, who continued to provide his services to British intelligence as a consultant while living in the idyllic surroundings of Wiltshire. Like the late Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London of radioactive poisoning in 2006, Skripal entrusted his personal safety to the British state. But in a country that today hosts nearly half a million Russians of all backgrounds and political persuasions, such a decision is exceedingly risky. from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success.

from abroad. It is, in other words, a simple weapon that can be dispensed using a simple method, with little risk to the assailant(s). It fits the profile of a state-sponsored covert killing: carefully planned and designed, yet simply executed, thus ensuring a high probability of success. Britain’s counterintelligence service is nearing the conclusion that a foreign government, most likely Russia, tried to kill a Russian double spy and his daughter, who are now fighting for their lives in a British hospital. Sergei Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia Skripal, 33, are said to remain in critical condition, after falling violently ill on Sunday afternoon while walking in downtown Salisbury, a picturesque cathedral city in south-central England. Skripal arrived in England in 2010 as part of a large-scale

Britain’s counterintelligence service is nearing the conclusion that a foreign government, most likely Russia, tried to kill a Russian double spy and his daughter, who are now fighting for their lives in a British hospital. Sergei Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia Skripal, 33, are said to remain in critical condition, after falling violently ill on Sunday afternoon while walking in downtown Salisbury, a picturesque cathedral city in south-central England. Skripal arrived in England in 2010 as part of a large-scale

Analysis: Decoding Britain’s response to the poisoning of Sergei Skripal

March 15, 2018 by Joseph Fitsanakis 8 Comments

Just hours after the attack on the Skripals, British defense and intelligence experts concluded that it had been authorized by the Kremlin. On Wednesday, Prime Minister May laid out a series of measures that the British government will be taking in response to what London claims was a Russian-sponsored criminal assault on British soil. Some of the measures announced by May, such as asking the home secretary whether additional counter-espionage measures are needed to combat hostile activities by foreign agents in the UK, are speculative. The British prime minister also said that the state would develop new proposals for legislative powers to “harden our defenses against all forms of hostile state activity”. But she did not specify what these proposals will be, and it may be months —even years— before such measures are implemented.

The primary direct measure taken by Britain in response to the attack against Skripal centers on the immediate expulsion of 23 Russian diplomats from Britain. They have reportedly been given a week to leave the country, along with their families. When they do so, they will become part of the largest expulsion of foreign diplomats from British soil since 1985, when London expelled 31 Soviet diplomats in response to revelations of espionage against Britain made by Soviet intelligence defector Oleg Gordievsky. Although impressive in size, the latest expulsions are dwarfed by the dramatic expulsion in 1971 of no fewer than 105 Soviet diplomats from Britain, following yet another defection of a Soviet intelligence officer, who remained anonymous.

the latest expulsions are dwarfed by the dramatic expulsion in 1971 of no fewer than 105 Soviet diplomats from Britain, following yet another defection of a Soviet intelligence officer, who remained anonymous.

It is important to note, however, that in 1971 there were more than 500 Soviet diplomats stationed in Britain. Today there are fewer than 60. This means that nearly 40 percent of the Russian diplomatic presence in the UK will expelled from the country by next week. What is more, the 23 diplomats selected for expulsion are, according to Mrs. May, “undeclared intelligence officers”. In other words, according to the British government, they are essentially masquerading as diplomats, when in fact they are intelligence officers, whose job is to facilitate espionage on British soil. It appears that these 23 so-called intelligence officers make up almost the entirety of Russia’s “official-cover” network on British soil. This means that the UK Foreign Office has decided to expel from Britain nearly every Russian diplomat that it believes is an intelligence officer. Read more of this post

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Analysis, diplomatic expulsions, Joseph Fitsanakis, Newstex, Russia, Russian embassy in the UK, Sergei Skripal, UK