Soviet memoirs suggest KGB abducted and murdered Swedish diplomat

September 13, 2016 1 Comment

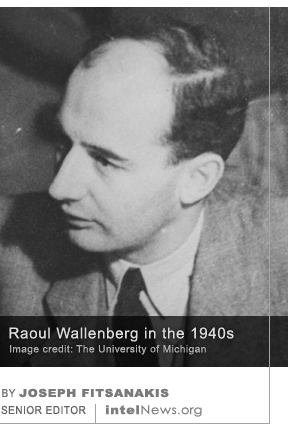

The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto.

The recently discovered memoirs of a former director of the Soviet KGB suggest that a senior Swedish diplomat, who disappeared mysteriously in the closing stages of World War II, was killed on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The fate of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is one of the 20th century’s unsolved espionage mysteries. In 1944 and 1945, the 33-year-old Wallenberg was Sweden’s ambassador to Budapest, the capital of German-allied Hungary. During his time there, Wallenberg is said to have saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazi concentration camps, by supplying them with Swedish travel documents, or smuggling them out of the country through a network of safe houses. He also reportedly dissuaded German military commanders from launching an all-out armed attack on Budapest’s Jewish ghetto.

But Wallenberg was also an American intelligence asset, having been recruited by a US spy operating out of the War Refugee Board, an American government outfit with offices throughout Eastern Europe. In January of 1945, as the Soviet Red Army descended on Hungary, Moscow gave orders for Wallenberg’s arrest on charges of spying for Washington. The Swedish diplomat disappeared, never to be seen in public again. Some historians speculate that Joseph Stalin initially intended to exchange Wallenberg for a number of Soviet diplomats and intelligence officers who had defected to Sweden. According to official Soviet government reports, Wallenberg died of a heart attack on July 17, 1947, while being interrogated at the Lubyanka, a KGB-affiliated prison complex in downtown Moscow. Despite the claims of the official Soviet record, historians have cited periodic reports that Wallenberg may have managed to survive in the Soviet concentration camp system until as late as the 1980s.

But the recently discovered memoirs of Ivan Serov, who directed the KGB from 1954 to 1958, appear to support the prevalent theory about Wallenberg’s demise in 1947. Serov led the feared Soviet intelligence agency under the reformer Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Joseph Stalin in the premiership of the USSR. Khrushchev appointed Serov to conduct an official probe into Wallenberg’s fate. Serov’s memoirs were found in 2012 by one of his granddaughters, Vera Serova, inside several suitcases that had been secretly encased inside a wall in the family’s summer home. According to British newspaper The Times, the documents indicate that Wallenberg was indeed held for two years in the Lubyanka, where he was regularly interrogated by the KGB. The latter were certain that the Swedish diplomat was an American spy who had also been close to Nazi Germany’s diplomatic delegation in Hungary. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin considered exchanging him for Soviet assets in the West. But eventually Wallenberg “lost his value [and] Stalin didn’t see any point in sending him home”, according to Serov’s memoirs. The KGB strongman adds that “undoubtedly, Wallenberg was liquidated in 1947”. Further on, he notes that, according to Viktor Abakumov, who headed the MGB —a KGB predecessor agency— in the mid-1940s, the order to kill Wallenberg came from Stalin himself.

In 2011, Lt. Gen. Vasily Khristoforov, Chief Archivist for the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), one of two successor agencies to the old Soviet KGB, gave an interview about Wallenberg, in which he said that most of the Soviet documentation on the Swedish diplomat had been systematically destroyed in the 1950s. But he said that historical reports of Wallenberg’s survival into the 1980s were “a product of […] people’s imagination”, and insisted that he was “one hundred percent certain […] that Wallenberg never was in any prison” other than the Lubyanka. An investigation by the Swedish government into the diplomat’s disappearance and eventual fate is ongoing.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 13 September 2016 | Permalink

The two sons of a Russian couple, who were among 10 deep-cover spies arrested in the United States, have given an interview about their experience for the first time. Tim and Alex Foley (now Vavilov) are the sons of Donald Heathfield and Tracey Foley, a married couple arrested in 2010 under Operation GHOST STORIES, a counterintelligence program run by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation. Following their arrest, their sons, who had grown up thinking their parents were Canadian, were told that they were in fact Russian citizens and that their real names were Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova. Their English-sounding names and Canadian passports had been

The two sons of a Russian couple, who were among 10 deep-cover spies arrested in the United States, have given an interview about their experience for the first time. Tim and Alex Foley (now Vavilov) are the sons of Donald Heathfield and Tracey Foley, a married couple arrested in 2010 under Operation GHOST STORIES, a counterintelligence program run by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation. Following their arrest, their sons, who had grown up thinking their parents were Canadian, were told that they were in fact Russian citizens and that their real names were Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova. Their English-sounding names and Canadian passports had been  A Russian former intelligence officer, who is accused by the British government of having killed another Russian former spy in London, said the British intelligence services tried to recruit him in 2006. British government prosecutors have charged Andrei Lugovoi with the killing of Alexander Litvinenko, a former employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor agencies, the FSB. In 2006, Litvinenko died in London, where he had defected with his family in 2000, following exposure to the highly radioactive substance Polonium-210. In July of 2007, the British government charged Lugovoi and another Russian, Dmitri Kovtun, with the murder of Litvinenko, and expelled four Russian diplomats from London. Last week, following the conclusion of an official inquest into the former KGB spy’s death, the British government took the unusual step of summoning the Russian ambassador to London, to file an official complaint about Moscow’s refusal to extradite Lugovoi and Kovtun to the United Kingdom.

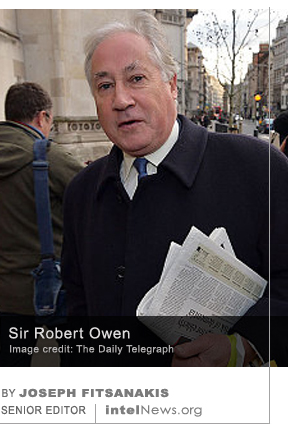

A Russian former intelligence officer, who is accused by the British government of having killed another Russian former spy in London, said the British intelligence services tried to recruit him in 2006. British government prosecutors have charged Andrei Lugovoi with the killing of Alexander Litvinenko, a former employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor agencies, the FSB. In 2006, Litvinenko died in London, where he had defected with his family in 2000, following exposure to the highly radioactive substance Polonium-210. In July of 2007, the British government charged Lugovoi and another Russian, Dmitri Kovtun, with the murder of Litvinenko, and expelled four Russian diplomats from London. Last week, following the conclusion of an official inquest into the former KGB spy’s death, the British government took the unusual step of summoning the Russian ambassador to London, to file an official complaint about Moscow’s refusal to extradite Lugovoi and Kovtun to the United Kingdom. The British government has taken the unusual step of summoning the Russian ambassador to London, following the conclusion of an official inquest into the death of a former KGB officer who is believed to have been killed on the orders of Moscow. Alexander Litvinenko, an employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor organizations, the FSB, defected with his family to the United Kingdom in 2000. But in 2006, he died of radioactive poisoning after meeting two former KGB/FSB colleagues, Dmitri Kovtun and Andrey Lugovoy, in London. A public inquiry into the death of Litvinenko, ordered by the British state,

The British government has taken the unusual step of summoning the Russian ambassador to London, following the conclusion of an official inquest into the death of a former KGB officer who is believed to have been killed on the orders of Moscow. Alexander Litvinenko, an employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor organizations, the FSB, defected with his family to the United Kingdom in 2000. But in 2006, he died of radioactive poisoning after meeting two former KGB/FSB colleagues, Dmitri Kovtun and Andrey Lugovoy, in London. A public inquiry into the death of Litvinenko, ordered by the British state,  The long-awaited concluding report of a public inquiry into the death of a former Soviet spy in London in 2006, is expected to finger the Russian state as the perpetrator of the murder. Alexander Litvinenko was an employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor organizations, the FSB, until 2000, when he defected with his family to the United Kingdom. He soon became known as a vocal critic of the administration of Russian President Vladimir Putin. In 2006, Litvinenko came down with radioactive poisoning after meeting two former KGB/FSB colleagues, Dmitri Kovtun and Andrey Lugovoy, at a London restaurant. In July of 2007, after establishing the cause of Litvinenko’s death, which is attributed to the highly radioactive substance Polonium-210, the British government officially charged the two Russians with murder and issued international warrants for their arrest. Whitehall also announced the expulsion of four Russian diplomats from London. The episode, which was the first public expulsion of Russian envoys from Britain since end of the Cold War, is often cited as marking the beginning of the worsening of relations between the West and post-Soviet Russia.

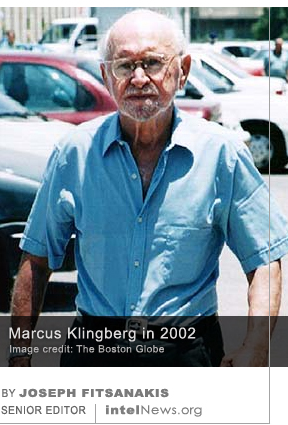

The long-awaited concluding report of a public inquiry into the death of a former Soviet spy in London in 2006, is expected to finger the Russian state as the perpetrator of the murder. Alexander Litvinenko was an employee of the Soviet KGB and one of its successor organizations, the FSB, until 2000, when he defected with his family to the United Kingdom. He soon became known as a vocal critic of the administration of Russian President Vladimir Putin. In 2006, Litvinenko came down with radioactive poisoning after meeting two former KGB/FSB colleagues, Dmitri Kovtun and Andrey Lugovoy, at a London restaurant. In July of 2007, after establishing the cause of Litvinenko’s death, which is attributed to the highly radioactive substance Polonium-210, the British government officially charged the two Russians with murder and issued international warrants for their arrest. Whitehall also announced the expulsion of four Russian diplomats from London. The episode, which was the first public expulsion of Russian envoys from Britain since end of the Cold War, is often cited as marking the beginning of the worsening of relations between the West and post-Soviet Russia. Marcus Klingberg, who is believed to be the highest-ranking Soviet spy ever caught in Israel, and whose arrest in 1983 prompted one of the largest espionage scandals in the Jewish state’s history, has died in Paris. Born Avraham Marek Klingberg in 1918, Klingberg left his native Poland following the joint German-Soviet invasion of 1939. Fearing persecution by the Germans due to his Jewish background, and being a committed communist, he joined the Soviet Red Army and served in the eastern front until 1941, when he was injured. He then received a degree in epidemiology from the Belarusian State University in Minsk, before returning to Poland at the end of World War II, where he met and married Adjia Eisman, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Together they moved to Sweden, from where they emigrated to Israeli in 1948. It is believed that Klingberg was recruited by the Soviet KGB while in Sweden, and that he moved to Israel after being asked to do so by his Soviet handlers –though he himself always denied it.

Marcus Klingberg, who is believed to be the highest-ranking Soviet spy ever caught in Israel, and whose arrest in 1983 prompted one of the largest espionage scandals in the Jewish state’s history, has died in Paris. Born Avraham Marek Klingberg in 1918, Klingberg left his native Poland following the joint German-Soviet invasion of 1939. Fearing persecution by the Germans due to his Jewish background, and being a committed communist, he joined the Soviet Red Army and served in the eastern front until 1941, when he was injured. He then received a degree in epidemiology from the Belarusian State University in Minsk, before returning to Poland at the end of World War II, where he met and married Adjia Eisman, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Together they moved to Sweden, from where they emigrated to Israeli in 1948. It is believed that Klingberg was recruited by the Soviet KGB while in Sweden, and that he moved to Israel after being asked to do so by his Soviet handlers –though he himself always denied it. A Russian former officer in the Soviet KGB, who defied deportation orders issued against him by the Canadian government by taking refuge in a Vancouver church for six consecutive years, has voluntarily left the country. Mikhail Lennikov, who spent five years working for the KGB in the 1980s, had been living in Canada with his wife and son since 1992. But in 2009, Canada’s Public Safety Ministry rejected Lennikov’s refugee claim and

A Russian former officer in the Soviet KGB, who defied deportation orders issued against him by the Canadian government by taking refuge in a Vancouver church for six consecutive years, has voluntarily left the country. Mikhail Lennikov, who spent five years working for the KGB in the 1980s, had been living in Canada with his wife and son since 1992. But in 2009, Canada’s Public Safety Ministry rejected Lennikov’s refugee claim and  A Soviet double spy, who secretly defected to Britain 30 years ago this month, has revealed for the first time the details of his exfiltration by British intelligence in 1985. Oleg Gordievsky was one of the highest Soviet intelligence defectors to the West in the closing stages of the Cold War. He joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, eventually reaching the rank of colonel. But in the 1960s, while serving in the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen, Denmark, Gordievsky began feeling disillusioned about the Soviet system. His doubts were reinforced by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was soon afterwards that he made the decision to contact British intelligence.

A Soviet double spy, who secretly defected to Britain 30 years ago this month, has revealed for the first time the details of his exfiltration by British intelligence in 1985. Oleg Gordievsky was one of the highest Soviet intelligence defectors to the West in the closing stages of the Cold War. He joined the Soviet KGB in 1963, eventually reaching the rank of colonel. But in the 1960s, while serving in the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen, Denmark, Gordievsky began feeling disillusioned about the Soviet system. His doubts were reinforced by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was soon afterwards that he made the decision to contact British intelligence.

Analysis: Is Putin planning to restore the Soviet-era KGB?

October 4, 2016 by intelNews Leave a comment

If the Kommersant article is accurate, Russia’s two main intelligence agencies will merge after an institutional separation that has lasted a quarter of a century. They were separated shortly after the official end of the Soviet Union, in 1991, when it was recognized that the KGB was not under the complete control of the state. That became plainly obvious in August of that year, when the spy agency’s Director, Vladimir Kryuchkov, helped lead a military coup aimed at deposing Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev. The two new agencies were given separate mandates: the SVR inherited the mission of the KGB’s foreign intelligence directorates and focused on collecting intelligence abroad; the FSB, on the other hand, assumed the KGB’s counterintelligence and counterterrorist missions. A host of smaller agencies, including the Federal Agency of Government Communications and Information (FAPSI), the Federal Protective Service (FSO) and others, took on tasks such as communications interception, border control, political protection, etc.

Could these agencies merge again after 25 years of separation? Possibly, but it will take time. An entire generation of Russian intelligence officers has matured under separate institutional roofs in the post-Soviet era. Distinct bureaucratic systems and structures have developed and much duplication has ensued during that time. If a merger was to occur, entire directorates and units would have to be restructured or even eliminated. Leadership roles would have to be purged or redefined with considerable delicacy, so as to avoid inflaming bureaucratic turf battles. Russian bureaucracies are not known for their organizational skills, and it would be interesting to see how they deal with the inevitable confusion of a possible merger. It could be argued that, if Putin’s goal is to augment the power of the intelligence services —which is doubtful, given their long history of challenging the power of the Kremlin— he would be better off leaving them as they are today.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 04 October 2016 | Permalink

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with Analysis, FSB, intelligence reform, Joseph Fitsanakis, KGB, Russia, SVR (Russia), USSR