German court sentences ex-Yugoslav spies to life for 1983 murder of dissident

August 4, 2016 Leave a comment

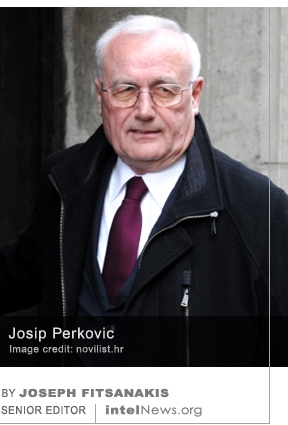

A German court has given life sentences to two senior intelligence officers in Cold-War-era Yugoslavia, who masterminded the murder of a Croat dissident in 1983. Josip Perković and Zdravko Mustać, both former senior officials in the Yugoslav State Security Service, known as UDBA, were extradited to Germany from Croatia in 2014. They were tried in a German court in the Bavarian capital Munich for organizing the assassination of Stjepan Đureković on July 28, 1983. Đureković’s killing was carried out by UDBA operatives in Wolfratshausen, Bavaria as part of an UDBA operation codenamed DUNAV. Đureković, who was of Croatian nationality, was director of Yugoslavia’s state-owned INA oil company until 1982, when he suddenly defected to West Germany. Upon his arrival in Germany, he was granted political asylum and began associating with Croatian nationalist émigré groups that were active in the country. It was the reason why he was killed by the government of Yugoslavia.

A German court has given life sentences to two senior intelligence officers in Cold-War-era Yugoslavia, who masterminded the murder of a Croat dissident in 1983. Josip Perković and Zdravko Mustać, both former senior officials in the Yugoslav State Security Service, known as UDBA, were extradited to Germany from Croatia in 2014. They were tried in a German court in the Bavarian capital Munich for organizing the assassination of Stjepan Đureković on July 28, 1983. Đureković’s killing was carried out by UDBA operatives in Wolfratshausen, Bavaria as part of an UDBA operation codenamed DUNAV. Đureković, who was of Croatian nationality, was director of Yugoslavia’s state-owned INA oil company until 1982, when he suddenly defected to West Germany. Upon his arrival in Germany, he was granted political asylum and began associating with Croatian nationalist émigré groups that were active in the country. It was the reason why he was killed by the government of Yugoslavia.

The court proceedings in Munich included dramatic testimony by another former UDBA operative, Vinko Sindicić, who named both Perković and Mustać as direct accomplices in Đureković’s murder. Sindicić told the court that Perković was acting on orders to kill the German-based dissident, which came directly from the office of UDBA Director Zdravko Mustać. He added that Perković helped organize the logistics of Đureković’s assassination, including the location in Munich where the killing actually took place. Sindicić told the court that a female UDBA operative living in Munich was also involved in organizing the operation, and that the weapons used to kill Đureković had been secretly transported to Germany through Jadroagent, an international shipping and freight company based in Yugoslavia.

On Wednesday, the court found both former UDBA officials guilty of complicity in the assassination of Đureković and convicted them for life. German media reported that the convicted men’s defense team plans to appeal the ruling by advancing the case to Germany’s Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe, Baden-Württemberg, which is Germany’s highest ordinary-jurisdiction court. Perković and Mustać declined requests to make comments to the press at the end of the trial. It is believed that at least 22 Croat nationalists were murdered in West Germany by the Yugoslavian intelligence services during the Cold War.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 04 August 2016 | Permalink

In a development that is reminiscent of the Cold War, a radio station in North Korea appears to have resumed broadcasts of encrypted messages that are typically used to give instructions to spies stationed abroad. The station in question is the Voice of Korea, known in past years as Radio Pyongyang. It is operated by the North Korean government and airs daily programming consisting of music, current affairs and instructional propaganda in various languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French, English, and Russian. Last week however, the station interrupted its normal programming to air a series of numbers that were clearly intended to be decoded by a few select listeners abroad.

In a development that is reminiscent of the Cold War, a radio station in North Korea appears to have resumed broadcasts of encrypted messages that are typically used to give instructions to spies stationed abroad. The station in question is the Voice of Korea, known in past years as Radio Pyongyang. It is operated by the North Korean government and airs daily programming consisting of music, current affairs and instructional propaganda in various languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French, English, and Russian. Last week however, the station interrupted its normal programming to air a series of numbers that were clearly intended to be decoded by a few select listeners abroad. A former officer in the Cold-War-era Yugoslav intelligence service has begun testifying at a trial concerning the 1983 murder in Germany of a Yugoslav dissident by assassins sent by authorities in Belgrade. Stjepan Đureković, who was of Croatian nationality, defected from Yugoslavia to Germany in 1982, while he was director of Yugoslavia’s state-owned INA oil company. Upon his arrival in Germany, he was granted political asylum and began associating with Croatian nationalist émigré groups that were active in the country. He was killed on July 28, 1983, in Wolfratshausen, Bavaria. His killing was part of an operation codenamed DUNAV, which was conducted by the Yugoslav State Security Service, known by its Serbo-Croatian acronym, UDBA.

A former officer in the Cold-War-era Yugoslav intelligence service has begun testifying at a trial concerning the 1983 murder in Germany of a Yugoslav dissident by assassins sent by authorities in Belgrade. Stjepan Đureković, who was of Croatian nationality, defected from Yugoslavia to Germany in 1982, while he was director of Yugoslavia’s state-owned INA oil company. Upon his arrival in Germany, he was granted political asylum and began associating with Croatian nationalist émigré groups that were active in the country. He was killed on July 28, 1983, in Wolfratshausen, Bavaria. His killing was part of an operation codenamed DUNAV, which was conducted by the Yugoslav State Security Service, known by its Serbo-Croatian acronym, UDBA. Recently uncovered documents shed further light on an ultra-secret plan, devised by the British and American governments, to destroy oil facilities in the Middle East in the event the region was invaded by Soviet troops. The

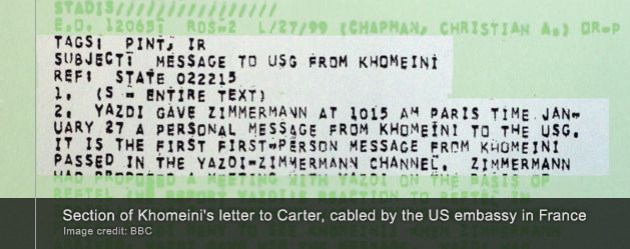

Recently uncovered documents shed further light on an ultra-secret plan, devised by the British and American governments, to destroy oil facilities in the Middle East in the event the region was invaded by Soviet troops. The  Newly declassified files show that Ayatollah Khomeini, who led Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, had a secret channel of communication with the United States, and even sent a personal letter to US President Jimmy Carter. On January 16, 1979, after nearly a year of street clashes and protests against his leadership, the king of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, fled the country for the US. His decision to leave was strongly influenced by his American advisors, who feared that Iran was heading toward a catastrophic civil war. The Shah’s departure did little to calm tensions in the country. Protesters —many of them armed— engaged in daily street battles with members of the police and the military, who remained loyal to Pahlavi. Meanwhile, a national strike had brought the Iranian oil sector to a standstill, thereby threatening to bring about a global energy crisis. Moreover, the country was home to thousands of American military advisors and the Iranian military was almost exclusively funded and supplied by Washington. The Carter administration worried that the weaponry and technical knowledge might fall into the hands of a new, pro-Soviet government in Tehran.

Newly declassified files show that Ayatollah Khomeini, who led Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, had a secret channel of communication with the United States, and even sent a personal letter to US President Jimmy Carter. On January 16, 1979, after nearly a year of street clashes and protests against his leadership, the king of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, fled the country for the US. His decision to leave was strongly influenced by his American advisors, who feared that Iran was heading toward a catastrophic civil war. The Shah’s departure did little to calm tensions in the country. Protesters —many of them armed— engaged in daily street battles with members of the police and the military, who remained loyal to Pahlavi. Meanwhile, a national strike had brought the Iranian oil sector to a standstill, thereby threatening to bring about a global energy crisis. Moreover, the country was home to thousands of American military advisors and the Iranian military was almost exclusively funded and supplied by Washington. The Carter administration worried that the weaponry and technical knowledge might fall into the hands of a new, pro-Soviet government in Tehran. Nine days later, on January 27, Dr. Yazdi gave Zimmerman a letter written by Khomeini and addressed to President Carter. The letter, which addressed Carter in the first person, was cabled to the Department of State from the US embassy in Paris and, according to the BBC, reached the US president. In the letter, Khomeini promises to protect “America’s interests and citizens in Iran” if Washington pressured the Iranian military to stand aside and allow him and his advisers to return to Iran. Khomeini’s fear was that the royalist Iranian military would not allow a new government to take hold in Tehran. But the exiled cleric was aware of America’s influence in Iranian military circles, which at the time were effectively under the command of General Robert Huyser, Deputy Commander of US Forces in Europe, who had been dispatched to Tehran by President Carter. Before answering Khomeini’s letter, the White House sent a draft response to the embassy in Tehran for input and advice. But Khomeini did not wait for Washington’s response. On February 1, he returned to Iran, where he was greeted by millions of people in the streets and welcomed as the next leader of the country. Meanwhile, Washington had already instructed General Huyser to rule out the so-called “option C”, namely a military coup carried out by the Iranian armed forces.

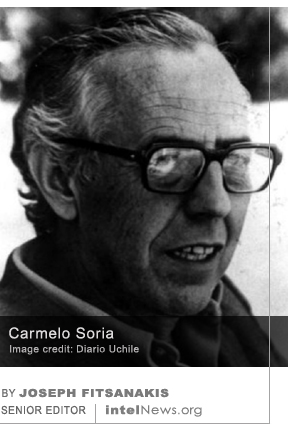

Nine days later, on January 27, Dr. Yazdi gave Zimmerman a letter written by Khomeini and addressed to President Carter. The letter, which addressed Carter in the first person, was cabled to the Department of State from the US embassy in Paris and, according to the BBC, reached the US president. In the letter, Khomeini promises to protect “America’s interests and citizens in Iran” if Washington pressured the Iranian military to stand aside and allow him and his advisers to return to Iran. Khomeini’s fear was that the royalist Iranian military would not allow a new government to take hold in Tehran. But the exiled cleric was aware of America’s influence in Iranian military circles, which at the time were effectively under the command of General Robert Huyser, Deputy Commander of US Forces in Europe, who had been dispatched to Tehran by President Carter. Before answering Khomeini’s letter, the White House sent a draft response to the embassy in Tehran for input and advice. But Khomeini did not wait for Washington’s response. On February 1, he returned to Iran, where he was greeted by millions of people in the streets and welcomed as the next leader of the country. Meanwhile, Washington had already instructed General Huyser to rule out the so-called “option C”, namely a military coup carried out by the Iranian armed forces. The Supreme Court of Chile will request that the United States extradites three individuals, including an American former professional assassin, who are implicated in the kidnapping, torture and murder of a United Nations diplomat. Carmelo Soria was a Spanish diplomat with dual Chilean nationality, who in the early 1970s was employed in the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1971, when the leftist Popular Unity party won Chile’s elections and became the nation’s governing coalition, Soria became an advisor to the country’s Marxist President, Salvador Allende. After the 1973 violent military coup, which killed Allende and overthrew his government, Soria used his diplomatic status to extend political asylum to a number of pro-Allende activists who were being hunted down by the new rightwing government of General August Pinochet.

The Supreme Court of Chile will request that the United States extradites three individuals, including an American former professional assassin, who are implicated in the kidnapping, torture and murder of a United Nations diplomat. Carmelo Soria was a Spanish diplomat with dual Chilean nationality, who in the early 1970s was employed in the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1971, when the leftist Popular Unity party won Chile’s elections and became the nation’s governing coalition, Soria became an advisor to the country’s Marxist President, Salvador Allende. After the 1973 violent military coup, which killed Allende and overthrew his government, Soria used his diplomatic status to extend political asylum to a number of pro-Allende activists who were being hunted down by the new rightwing government of General August Pinochet. The arrest of Nelson Mandela in 1962, which led to his 28-year incarceration, came after a tip from the United States Central Intelligence Agency, according to an American diplomat who was in South Africa at the time. At the time of his arrest, Mandela was the head of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), an organization he founded in 1961 to operate as the armed wing of the anti-apartheid African National Congress (ANC). But the white minority government of South Africa accused Mandela of being a terrorist and an agent of the Soviet Union. The US-Soviet rivalry of that era meant that the ANC and its leader had few supporters in America during the early stages of the Cold War.

The arrest of Nelson Mandela in 1962, which led to his 28-year incarceration, came after a tip from the United States Central Intelligence Agency, according to an American diplomat who was in South Africa at the time. At the time of his arrest, Mandela was the head of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), an organization he founded in 1961 to operate as the armed wing of the anti-apartheid African National Congress (ANC). But the white minority government of South Africa accused Mandela of being a terrorist and an agent of the Soviet Union. The US-Soviet rivalry of that era meant that the ANC and its leader had few supporters in America during the early stages of the Cold War. A videotaped lecture by Kim Philby, one of the Cold War’s most recognizable espionage figures, has been unearthed in the archives of the Stasi, the Ministry of State Security of the former East Germany. During the one-hour lecture, filmed in 1981, Philby addresses a select audience of Stasi operations officers and offers them advice on espionage, drawn from his own career. While working as a senior member of British intelligence, Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as ‘Kim’ to his friends, spied on behalf of the Soviet NKVD and KGB from the early 1930s until 1963, when he secretly defected to the USSR from his home in Beirut, Lebanon. Philby’s defection sent ripples of shock across Western intelligence and is often seen as one of the most dramatic moments of the Cold War.

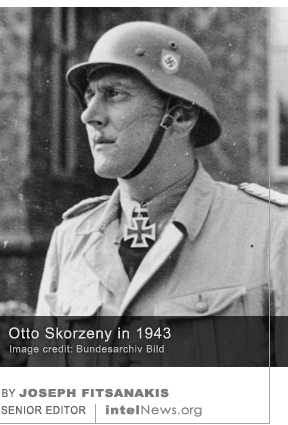

A videotaped lecture by Kim Philby, one of the Cold War’s most recognizable espionage figures, has been unearthed in the archives of the Stasi, the Ministry of State Security of the former East Germany. During the one-hour lecture, filmed in 1981, Philby addresses a select audience of Stasi operations officers and offers them advice on espionage, drawn from his own career. While working as a senior member of British intelligence, Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as ‘Kim’ to his friends, spied on behalf of the Soviet NKVD and KGB from the early 1930s until 1963, when he secretly defected to the USSR from his home in Beirut, Lebanon. Philby’s defection sent ripples of shock across Western intelligence and is often seen as one of the most dramatic moments of the Cold War. A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government.

A notorious lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, who served in Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, worked as a hitman for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad after World War II, it has been revealed. Austrian-born Otto Skorzeny became known as the most ruthless special-forces commander in the Third Reich. Having joined the Austrian branch of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party at 19, at age 23 Skorzeny began serving in the Waffen SS, Nazi Germany’s conscript army that consisted largely of foreign-born fighters. In 1943, Hitler himself decorated Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, in recognition of his leadership in Operation EICHE, the rescue by German commandos of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been imprisoned at a ski resort in the Apennine Mountains following a coup against his government. Two teams of international experts will examine the exhumed remains of Chilean Nobel Laureate poet Pablo Neruda, who some say was deliberately injected with poison by the Chilean intelligence services. The literary icon died on September 23, 1973, less than two weeks after a coup d’état, led by General Augusto Pinochet, toppled the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende, a Marxist who was a close friend of Neruda. The death of the internationally acclaimed poet, who was 69 at the time, was officially attributed to prostate cancer and the effects of acute mental stress caused by the military coup. In 2013, however, an

Two teams of international experts will examine the exhumed remains of Chilean Nobel Laureate poet Pablo Neruda, who some say was deliberately injected with poison by the Chilean intelligence services. The literary icon died on September 23, 1973, less than two weeks after a coup d’état, led by General Augusto Pinochet, toppled the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende, a Marxist who was a close friend of Neruda. The death of the internationally acclaimed poet, who was 69 at the time, was officially attributed to prostate cancer and the effects of acute mental stress caused by the military coup. In 2013, however, an  Switzerland secretly agreed in the 1970s to support calls for Palestinian statehood, in return for not being targeted by Palestinian militants, according to a new book. Written by Marcel Gyr, a journalist with the Zurich-based Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the book

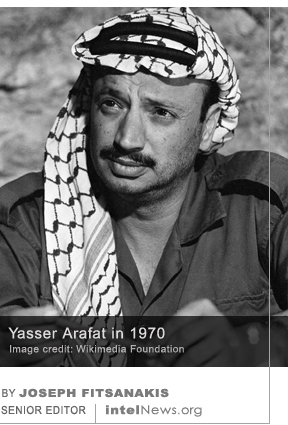

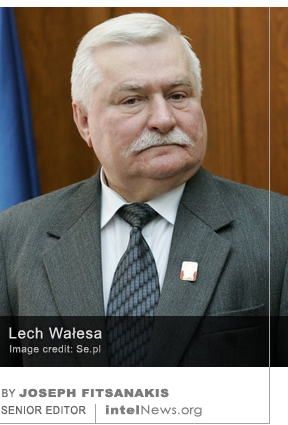

Switzerland secretly agreed in the 1970s to support calls for Palestinian statehood, in return for not being targeted by Palestinian militants, according to a new book. Written by Marcel Gyr, a journalist with the Zurich-based Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the book  Poland’s first post-communist president, Lech Wałęsa, has denied allegations that he was secretly a communist spy and has called for a public debate so he can respond to his critics. In 1980, when Poland was still under communist rule, Wałęsa was among the founders of Solidarność (Solidarity), the communist bloc’s first independent trade union. After winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, Wałęsa intensified his criticism of Poland’s communist government. In 1990, following the end of communist rule, Wałęsa, was elected Poland’s president by receiving nearly 75% of the vote in a nationwide election. After stepping down from the presidency, in 1995, Wałęsa officially retired from politics and is today considered a major Polish and Eastern European statesman.

Poland’s first post-communist president, Lech Wałęsa, has denied allegations that he was secretly a communist spy and has called for a public debate so he can respond to his critics. In 1980, when Poland was still under communist rule, Wałęsa was among the founders of Solidarność (Solidarity), the communist bloc’s first independent trade union. After winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, Wałęsa intensified his criticism of Poland’s communist government. In 1990, following the end of communist rule, Wałęsa, was elected Poland’s president by receiving nearly 75% of the vote in a nationwide election. After stepping down from the presidency, in 1995, Wałęsa officially retired from politics and is today considered a major Polish and Eastern European statesman. A tightly knit group of Dutch technical experts helped American spies bug foreign embassies at the height of the Cold War, new research has shown. The research, carried out by Dutch intelligence expert Cees Wiebes and journalist Maurits Martijn, has brought to light a previously unknown operation, codenamed EASY CHAIR. Initiated in secret in 1952, the operation was a collaboration between the United States Central Intelligence Agency and a small Dutch technology company called the Nederlands Radar Proefstation (Dutch Radar Research Station).

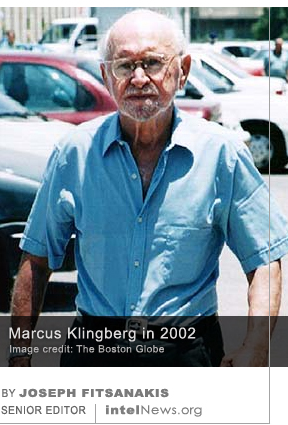

A tightly knit group of Dutch technical experts helped American spies bug foreign embassies at the height of the Cold War, new research has shown. The research, carried out by Dutch intelligence expert Cees Wiebes and journalist Maurits Martijn, has brought to light a previously unknown operation, codenamed EASY CHAIR. Initiated in secret in 1952, the operation was a collaboration between the United States Central Intelligence Agency and a small Dutch technology company called the Nederlands Radar Proefstation (Dutch Radar Research Station). Marcus Klingberg, who is believed to be the highest-ranking Soviet spy ever caught in Israel, and whose arrest in 1983 prompted one of the largest espionage scandals in the Jewish state’s history, has died in Paris. Born Avraham Marek Klingberg in 1918, Klingberg left his native Poland following the joint German-Soviet invasion of 1939. Fearing persecution by the Germans due to his Jewish background, and being a committed communist, he joined the Soviet Red Army and served in the eastern front until 1941, when he was injured. He then received a degree in epidemiology from the Belarusian State University in Minsk, before returning to Poland at the end of World War II, where he met and married Adjia Eisman, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Together they moved to Sweden, from where they emigrated to Israeli in 1948. It is believed that Klingberg was recruited by the Soviet KGB while in Sweden, and that he moved to Israel after being asked to do so by his Soviet handlers –though he himself always denied it.

Marcus Klingberg, who is believed to be the highest-ranking Soviet spy ever caught in Israel, and whose arrest in 1983 prompted one of the largest espionage scandals in the Jewish state’s history, has died in Paris. Born Avraham Marek Klingberg in 1918, Klingberg left his native Poland following the joint German-Soviet invasion of 1939. Fearing persecution by the Germans due to his Jewish background, and being a committed communist, he joined the Soviet Red Army and served in the eastern front until 1941, when he was injured. He then received a degree in epidemiology from the Belarusian State University in Minsk, before returning to Poland at the end of World War II, where he met and married Adjia Eisman, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Together they moved to Sweden, from where they emigrated to Israeli in 1948. It is believed that Klingberg was recruited by the Soviet KGB while in Sweden, and that he moved to Israel after being asked to do so by his Soviet handlers –though he himself always denied it.

CIA agent was among Watergate burglars, documents reveal

August 31, 2016 by Joseph Fitsanakis 20 Comments

Soon after the Watergate scandal erupted, the CIA produced an internal report entitled “CIA Watergate History – Working Draft”. Much of the 150-page document was authored by CIA officer John C. Richards, who had firsthand knowledge of the Watergate scandal. When Richards died unexpectedly in 1974, the report was completed by a team of officers based on his files. A few years ago, a Freedom of Information Act request was filed by Judicial Watch, a conservative legal watchdog, which petitioned to have the document released. The release was approved by a judge in early 2016 and was completed in July.

Despite numerous reductions throughout, the document gives the fullest public account of the CIA’s role in the Watergate scandal. Its pages contain the revelation that one of the men arrested in the early hours of June 17, 1972, was an active CIA agent. The man, Eugenio R. Martinez, has been previously identified as an “informant” of the CIA —a term referring to an occasional source. But the newly released document refers to Martinez as an agent —an individual who is actively recruited and trained by a CIA officer acting as a handler. It also states that Martinez was on the payroll of the agency at the time of his arrest, making approximately $600 per month in today’s dollars working for the CIA. Additionally, Martinez, a Cuban who had participated in the Bay of Pigs invasion, retained his contacts with the CIA and kept the agency updated about the burglary, his arrest and the ensuing criminal investigation.

Interestingly, the internal document reveals that the CIA was contacted about Martinez by the Watergate Special Prosecution Force, which was set up by the Department of Justice to investigate the scandal. But the CIA’s General Counsel, John S. Warner, told the prosecutors that it was against the CIA’s code of practice to turn over an agent, and that “under no circumstances” would the CIA agree to do so. Senior CIA officials, including its then Director, Richard Helms, continued to refuse to cooperate with investigators, including agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, even after President Nixon’s resignation.

Martinez, who is reportedly in his mid-90s and lives in Miami, Florida, has never spoken publicly about this role in the Watergate scandal or his alleged contacts with the CIA.

► Author: Joseph Fitsanakis | Date: 31 August 2016 | Permalink

Filed under Expert news and commentary on intelligence, espionage, spies and spying Tagged with CIA, declassification, Eugenio R. Martinez, history, Judicial Watch, News, Watergate